- Home

- Ursula Hegi

The Worst Thing I've Done

The Worst Thing I've Done Read online

Also By Ursula Hegi

Sacred Time

Hotel of the Saints

The Vision of Emma Blau

Tearing the Silence

Salt Dancers

Stones from the River

Floating in My Mother’s Palm

Unearned Pleasures and Other Stories

Intrusions

Trudi & Pia

TOUCHSTONE

A Division of Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, New York 10020

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or person, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2007 by Ursula Hegi

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Touchstone Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Touchstone hardcover edition October 2007

TOUCHSTONE and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc.

Designed by Joy O’Meara

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hegi, Ursula.

The worst thing I’ve done : a novel / Ursula Hegi.

p. cm.

“A Touchstone Book.”

I. Title

PS35583E4185W67 2007

813′.54—dc22

2006101171

ISBN-10: 1-4165-5451-3

ISBN-13: 978-1-4165-5451-6

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

for Gail Hochman and Mark Gompertz

Acknowledgments

A special thank-you to Nan Orshefsky, who took me into her studio and taught me about collages, and to Gordon Gagliano, who took me inside the creative process of a visual artist. They both, along with Barbara Wright, commented on early drafts. I thank Mike Bottini because I keep learning from his books about the natural history of the East End.

As always, immeasurable thanks to Gail Hochman, my brilliant agent of twenty-eight years, and to Mark Gompertz, who has edited my books with such wisdom for the past thirteen years.

One

Annie

{ Talk Radio }

TONIGHT, ANNIE is driving from North Sea to Montauk and back to North Sea as she has every night since Mason killed himself. She turns on the radio. Finds Dr. Francine. Listening to people so desperate that they confess their misery to radio psychologists distracts Annie from the rope cutting into Mason’s graceful neck, his flat ears lovely even in death. Distracts her for a few minutes—but only late at night, alone in her car, when she can be as anonymous as those callers.

Annie switches between Dr. Francine and Dr. Virginia during long commercials for anti-itch powder and ointments guaranteed to cure various sores. Dr. Virginia is snappy, cuts people off, tells them the solutions to their problems before they finish describing their problems. But Dr. Francine’s voice is soothing. Whenever she sighs, you can feel her compassion, even for those callers who go on and on…like this shaky voice now, Linda from Walla Walla, Washington—talking about shrimp.

“Everyone in Walla Walla knows. Fifty-two years ago I stole a bag of shrimp from the grocery store. I don’t know why, Dr. Francine. I was looking at them on display, so…curved and so pink.” There’s something oddly sexual in Linda’s description of the curved pink flesh. A pink, curved longing…

Dr. Francine sighs. Annie can tell she’s a good listener. Imagines a gentle face, lined and intelligent.

“It’s the only time I ever…stole anything, Doctor. The store manager, she told me to unzip my coat…”

Annie turns from Towd Point onto Noyack Road. Clear. The sky too. Clear, with just a fist of clouds around the moon.

“…because that’s were I was hiding the shrimp, inside my fur coat, not real mink, Dr. Francine, fun fur. The manager said she’d see me in court, but no one came for me though I kept waiting, and all along my husband’s mother saying she warned him before he married me. Lately…”

“Yes, Linda?”

“Lately, I’ve had the feeling everyone is talking about me and those shrimp.”

“Even after half a century?” Dr. Francine asks softly.

“I’ve stopped leaving my house because people are teasing me about it.”

“What do they say to you, Linda?”

“Oh, nothing directly to me, really…”

“Space cookie heaven.” Mason’s voice. From inside the radio?

“No.” That’s why Annie is in the car—to get away from him. The steering wheel vibrates under her palms as the speedometer zooms to fifty on the winding road.

“Space cookie heaven.” Mason, humming Twilight Zone inside Annie’s head—

“FUCK OFF, Mason.”

“In my heart I’ll always be married to you.”

“That’s so…arrogant.”

Her headlights skim across a diamond-shaped road sign with the silhouette of a deer leaping left to right. Always left to right. She’s on the stretch of road with water on both sides. For an instant she wonders—would it stop her rage if she were to twist the steering wheel to the right and slide into North Sea Harbor? Not for me. She taps the brakes. Having a child didn’t stop Mason. With him, there always was that wildness, that fiery energy Annie used to love because it electrified their marriage. But for her all wildness ceased eight years ago, when Opal was born. That’s why she drives fast, but not dangerously so. Because of Opal. Who is finally asleep at Aunt Stormy’s house in North Sea, where they’ve stayed in the seventeen days since Mason’s death.

Some nights it takes hours to get Opal settled because she keeps calling Annie to her bed. Knee aches. Head aches. Ache aches. All kinds of little complaints to bring Annie back to her. Tonight, a thumb ache. And when Annie held her, she felt Opal shiver, felt her own fierce love for Opal like a shiver, a blink, throughout her body, always part of her.

“Burn in hell, you bastard, for doing this.”

Mason’s parents arranged his funeral. Even though, as his wife, it was Annie’s choice what to do. They asked her. A burial in earth? Cremation? She was grateful when they decided, and she returned to New Hampshire to stand with them, and Jake, at her husband’s grave site.

It used to be safe, hugging Jake.

“AND THAT uneasiness just started lately, Linda?” Dr. Francine asks.

“Well…I was ashamed for a few years after it happened, but then I didn’t think about shrimp much…until lately.”

Another sigh. “I can tell how this one incident has poisoned your entire life, but it doesn’t have to be that way, dear.”

Now if Dr. Virginia were taking this call, she would have interrupted Linda long ago, telling her, “You’re probably getting ready to steal again.” Annie can tell right away which station she has, because if the caller is talking, it must be Dr. Francine’s show, and if the doctor is talking, it must be Dr. Virginia’s.

Annie can see Linda, smuggling a bag of embryonic shrimp inside her fun-fur coat. She’d bet ten dollars Linda never had children.

“Twelve dollars,” Mason says. “I bet you twelve that she has at least one kid.”

“I bet you fifteen. And no children. Maybe shrimp-size miscarriages. No full-term children.”

“Twenty. That she has one full-term child. Maybe more.”

They used to bet on anything, she and Mason. What color the desk clerk’s hair would be as they checked into a hotel. What hour of the day their phone would ring first. And all those bets about Opal. Would her eyes stay blue? Her hair re

d like Annie’s? How many weeks before she’d sleep through the night? At what age she’d take her first step. What her favorite food would be. And they both paid up, shifting the winnings between them.

“I BET YOU eight dollars she’ll turn over on her tummy before Friday.” Mason was holding Opal in the cradle of his arm, nudging the bottle between her gums just so.

“Ten dollars she’ll turn over Saturday or Sunday,” Annie said.

His lips were puckering.

Annie laughed. “Are you doing the swallowing for her?”

“I am. Do you think she’s unusual?”

“What way?”

“More aware than other babies. The way she observes us.” He rubbed Opal’s tummy.

“You sound like a proud parent.”

“Proud like entitlement-parent-proud?”

“Valid-proud, Mason.” Annie traced the side of Opal’s face, from her temple down to her pointed chin, as if she were sketching her. The same pointed chin that Annie and her mother had too.

“How about me?” Mason asked.

She stroked his temple, his ear and chin and neck.

“Hey…” He smiled at her.

Milk trickled from Opal’s mouth. She was sturdy like Annie, graceful like Mason.

“Keep that suction going now. Have I ever told you that I’m crazy about start-up humans?” His thumb kept making circles on Opal’s tummy. “Right, Startup?”

And that became his first endearment for her: Startup.

Startup became Stardust.

Became Dustmop when she played in the sandbox.

Mophead when she was tousled by wind.

IF ANNIE were to call one of the radio doctors—not that she would—it would definitely not be Dr. Virginia, but Dr. Francine, who’d understand why Annie wanted away from Mason. But then, of course, he beat her to it—he’d always been competitive—got away from her in the rough and sudden way that left her with the blame and the rage and the loss of everything golden between them.

Because that was how it started, knowing each other in that golden way before they were old enough to talk—she born in August; he in December of the same year to the piano teacher and the banker next door. A history of knowing each other.

Her first memory one of touch: her fingers on Mason’s toes, stroking…pinching…

Her second memory: toddling alongside Mason’s father, who was pushing Mason in his stroller and saying, “Hold on tight, Annabelle.”

Hold on tight.

His last name was Piano, and Annie’s dad liked to say he didn’t know if Mr. Piano had changed his name to Piano because he was a piano teacher, or if he had become a piano teacher because of that name. Mr. and Mrs. Piano were tall and elegant, their blue-black hair touching their shoulders.

“Expensive haircuts,” Annie’s dad would say, “but cheap furniture.”

Mr. Piano had his hair in a ponytail. The only stay-at-home dad in the neighborhood, he wore a suit and vest around the house. It made him look like a banker, which was weird, because Mrs. Piano was a banker but looked like a piano teacher, with her long fingers and long scarves.

A black scarf at the cemetery. A black scarf over a black coat. And her fingers twisted into the end of that scarf. “Come home with us, Annie.”

“Opal, I need to get…home to Opal.”

“I understand. It’s a long drive.”

“But I’ll come back another time.”

“Bring Opal,” Mrs. Piano said.

“Soon.”

“And Jake,” Mr. Piano said. “There’s something we need to ask you.”

WHEN ANNIE was three, she and Mason pulled each other around in Jake’s red wagon. His house was one house from Mason’s, two from Annie’s, and his mother was the babysitter for several kids in the neighborhood. A science teacher, she’d started day care because she wanted to be home with Jake. She laughed easily, was forever patient, and made any lunch the children wanted: waffles or ham omelets or egg salad or peanut butter with Fluff.

Jake’s father worked for Sears. “An almost handsome man,” Annie once heard her mother say to Mason’s mother, and they laughed. “With a face that’s just a little off because his features are tipped sideways—”

“Sideways?”

“You know, toward the left side of his jaw?”

“Still, he is the best-looking man on our block,” Mason’s mother said. “Sort of…rakish.”

If Mason asked for a lunch no one else asked for, Jake would say, “Whatever the other kids are having, Mama.” After lunch he’d help her clean up, while Mason ran around her kitchen, yelling, “I want I want I want—” yelling it fast as if he couldn’t figure out what he wanted—only that he wanted.

Jake would watch him, eyes sullen. But one day he stepped into Mason’s way. “You’re not the boss of her.”

“Remember now—” His mother pulled Jake close, kissed the top of his white-blond hair. “Mason is a paying guest.”

Paying guest. Annie’s neck felt sweaty. Salty. Sometimes her parents paid late. “Not because they don’t have enough money,” she’d heard Jake’s mother say, “but because they’re careless. They can’t imagine people needing the money they earned that day.”

“LINDA? I want you to try and remember,” Dr. Francine says, “if anything has changed in your life recently to bring up that shame. And I promise we’ll talk about that right after this message from our sponsor.”

“I still don’t eat shrimp.” In her voice, again, that pink, curved longing.

“Please—” Mason says, “Don’t even think about pink, curved longing.”

And then it’s the woman who sells tooth whitener, money-back guarantee, favored by celebrities around the globe. Flutes and harps rise above her recital of grisly side effects, making them sound beneficial.

Since the commercials are longer than the advice sessions, Annie switches to Dr. Virginia.

“—and you must examine your own role in this, Frank,” Dr. Virginia says.

“All I know is my wife got home ten minutes ago smelling of—”

“Frank, I do not need to hear any more.”

“But she was smelling of another man and she did it to get even because I got together that one time only with my first ex-wife and—”

“What you are telling me, Frank, is definitely a case of—”

“—that’s when I informed her I’ll call you Dr. Virginia—see she listens to you all day long at the office and keeps quoting you to me—”

“You are not listening to me, Frank. Your wife is obviously an intelligent woman who thinks independently. Tell her thank you from me.”

“—so I figured you could tell me where I can take my wife to get a test done to see if she was with another man and—”

“How long have you been married, Frank?”

“Five months and if I tell her you said to get the test she’ll do it because of you and—”

“At one A.M.?” Dr. Virginia sounds impatient to get to the buy-me-now commercials. “First of all, a test is not going to resolve what is truly going on between the two of you. It is an issue of trust, of you not—”

“But she just got back from having sex Dr. Virginia and there should be a trace if we do the test right away like an X-ray or peeing into a cup or—”

“You are interrupting me again, Frank.”

“Sorry. I keep telling my wife one more time and that’s it and—”

“Frank—”

“—it only makes her go to bars even though she knows—”

“Frank. Frank. Are you listening to a word I am saying?”

“Sure but—”

“Do you ever listen to your wife? Your problem is communication, and this jealousy of yours is sabotaging your marriage—”

“LET MEtell you about jealousy,” Annie interrupts Dr. Virginia. “About finding a penny on Mason’s side of the bed…just a couple of months ago, while he and Aunt Stormy were in Washington, D.C., to protest any preemp

tive attack on Iraq. When he came home, I asked him about the penny, and he told me he didn’t know anything about it…but then he admitted he’d put it there…three feet from the foot end…because I sleep on the futon in the living room whenever he’s gone. He said if the penny had been moved or the sheets changed, it meant I had another man there and—”

“I want both of you to go to sleep now,” Dr. Virginia prescribes.

“I was stunned,” Annie says. “Then furious. Told him he was twisted inside. That my loving him was never enough for him.”

“And in the morning I expect you to look for a marriage therapist.”

“Too late for that,” Mason says.

“Unless of course you don’t care to save that marriage of yours, Frank.”

“If I knew from a test that my wife didn’t sleep with someone else I’d feel more trusting.”

As Annie drives into darkness, taking back roads wherever she can, her headlights cast pale gray circles on the black pavement. She’s been driving this same loop every night: west from North Sea to Riverhead, then east on Route 27 as far as it goes to Montauk Point, from there west to North Sea, where Aunt Stormy lives at the end of a long, bumpy driveway, a strip of weeds down the middle. Big old trees. A hammock. From the driveway you can see her cottage and Little Peconic Bay all at once…see the bay through the windows of her cottage and on both sides of the cottage, silver-gray barn siding, bleached. Inside, a dried rose woven into a piece of driftwood hangs from the candle chandelier, along with delicate glass balls.

Annie doesn’t want Opal to know she’s out driving. But Aunt Stormy knows. Aunt Stormy said, “It’s what you need for the time being.”

“AND WHAT will it be next, Frank?” Dr. Virginia asks. “A test once a week to see if your wife has stayed faithful?”

“Do they have those?”

“There are no tests for trust.”

“Right.” Annie slaps the rim of the steering wheel and thinks of a day, early in her marriage, when she bought herself a golden neck chain to celebrate the sale of two collages from her Pond Series.

Ursula Hegi the Burgdorf Cycle Boxed Set

Ursula Hegi the Burgdorf Cycle Boxed Set The Worst Thing I've Done

The Worst Thing I've Done Stones From the River

Stones From the River Hotel of the Saints

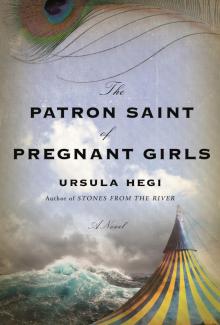

Hotel of the Saints The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls

The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls