- Home

- Ursula Hegi

Hotel of the Saints

Hotel of the Saints Read online

Praise for Ursula Hegi and Hotel of the Saints

“Ursula Hegi is a tumbledown, headlong sort of writer. Her words rush out… like children rolling down a hill, laughing. She unpeels her characters like artichokes.”

— Susan Salter Reynolds, Los Angeles Times

“[Hegi’s] talent for crafting a memorable short story seems confirmed…. Her gift for offbeat characters, humor, and authenticity turns up again in Hotel of the Saints.”

—Amy Graves, The Boston Globe

“Ursula Hegi’s gifts can conjure up an entire universe of loneliness and yearning, of self-delusion and suffering, in the space of four pages…. [She] is a compelling storyteller with a capacious heart, irreverent wit, and a keenly observant eye. She finds meaning in the smallest wrinkles of everyday existence, never patronizing her characters or her readers. Her tiny canvases teem with life.”

—Whitney Gould, The San Diego Union-Tribune

“These are little crystals of human interaction, some brittle and cool, others throbbing with light.”

— Karen Valby, Entertainment Weekly

“Ursula Hegi… writes short stories as adeptly as she does novels. Like a Polaroid picture brimming with sharp detail in only minutes, Hegi’s characters and settings achieve intimacy and credibility in a few pages…. Each [story] is engaging and heartfelt.”

—Nancy Jacobsen, Rocky Mountain News

“Finely wrought fables with transcendent resolutions… a vivid imagination and luminous writing.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Charming, low-key stories… Hegi writes with a gentle wit and an obvious affection for her offbeat characters, but it is the gracefully imparted details—tiny bubbles on the skin seen in the underwater light of a swimming pool, or the sunny, dusty smell of a dog’s fur—that make her stories come brilliantly to life.”

—Carrie Bissey, Booklist

“[Hegi] writes convincingly about the mysteries of the heart… [T]here are stories here that deliver a solar plexus punch.”

— Beth Kephart, Book Magazine

“Hegi is a literary photographer of the heart. [Her] voice … is strong, varied, and beautiful. Readers of Hegi’s highly regarded novels won’t be disappointed and one hopes another ten years won’t slip by before she publishes another collection. Highly recommended.”

—Beth Andersen, Library Journal

“Enchanting, stirring, and written with emotional intensity and grace…. Hegi is a first-class storyteller.”

—Larry Lawrence, The Abilene (Texas) Reporter-News

Other Books by Ursula Hegi

The Vision of Emma Blau

Tearing the Silence

Salt Dancers

Stones from the River

Floating in My Mother’s Palm

Unearned Pleasures and Other Stories

Intrusions

Scribner

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2001 by Ursula Hegi

Previously published in different format.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

First Scribner ebook edition May 2011

SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc. used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Designed by

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ISBN 978-1-4391-4365-0

Some of the stories in this collection appeared in the following periodicals: Hotel of the Saints, Story; The End of All Sadness, Triquarterly; A Woman’s Perfume, originally published as Collaborators, Louisville Review; Doves, Praire Schooner; Freitod, Ms.; A Town Like Ours, Praire Schooner; The Juggler, Story; For Their Own Survival, Loiusville Review. Stolen Chocolates was a selection of the Syndicated Fiction Project.

Acknowledgments

As always, I have valued the insights and comments I’ve received while working on these stories. A special thank you to my agents, Gail Hochman and Marianne Merola; to my editor, Mark Gompertz; to Olivia Caulliez, Deb Harper, Sue Mullen, and David Weekes; and to my husband, Gordon Gagliano.

For my son Adam

Contents

Hotel of the Saints

The End of All Sadness

A Woman’s Perfume

Stolen Chocolates

Doves

Freitod

Moonwalkers

A Town Like Ours

The Juggler

For Their Own Survival

Lower Crossing

Hotel of the Saints

Hotel of the Saints

Lenny’s mother, the starch queen, is baking for her brother’s funeral: cinnamon cookies and blackberry pies, garlic bread and her own recipe of poppyseed strudel. Lenny loves watching his mother’s freckled fists pummel the dough. Next to her, he feels anemic in his seminary clothes.

Across the kitchen, her two sisters are also baking to see their one brother, Leonard, off according to parish tradition — the bake-off of the starch sisters.

Early on, Lenny learned to dodge his Uncle Leonard, who was far too fussy and pious for him, who took it upon himself to fill the father role in Lenny’s life, who gave him his name at birth, holy cards from his hotel gift shop on Easter Sundays, and a pocket watch when Lenny entered the Jesuit seminary four years ago.

“In a family of women,” Uncle Leonard liked to say, “it’s important for a boy to look up to a man.”

But by the time Lenny was eleven, he was already half a head taller than his uncle and felt far more comfortable with the women in the family. The starch queen—after an impulsive marriage in her late thirties—had divorced Lenny’s father, Otis, two months before Lenny was born, eager to return to her sisters, who’d never married, and continue the pattern of their childhood. The Taluccio sisters always were close: when they were girls, they insisted on sharing the turret room on the third floor of their old Victorian by the Willamette River in Portland. Now each sister has a cluster of rooms she calls her own, but they convene in the tiled kitchen and on the wide porch that envelops three sides of the house.

Slender, strong women with firm arms, the Taluccio sisters laugh too loudly and slap men’s backs when they greet them. They seldom speak of Otis, who moved away from Portland after the divorce and has never contacted the starch queen or his child. When Lenny was a boy, they sometimes saw the yearning for his father in his eyes, and they answered whatever questions he had about Otis—how Otis hated the rain; how Otis liked raspberries mixed in with sliced bananas; how Otis had a cat named Muffy when he was a boy; how Otis liked to drive with the windows open—and they helped Lenny imagine Otis in some dry, warm climate, working in a marina, or a car dealership. Amongst themselves, though, the starch sisters are sure Otis just continued to drift from one unemployment line to another, braking for spells of work just long enough to qualify him, once again, for unemployment checks.

Now that t

hey’re retired from their jobs at the post office and fabric shop and hardware store, the starch sisters like to play cards late into the night—just the three of them—sitting around the kitchen table with a bowl of pretzels and a bottle of Chianti. They pray with the same passion that they bring to their food and their card games, and they take pride in still belonging to the parish where they were christened, a parish so poor that the altar society has only one change of clothing for the Infant of Prague statue.

With their sister-in-law, Jocelyn, the starch sisters are patient, although she horrifies them with her helplessness. Forty years earlier, on her honeymoon, Lenny’s Aunt Jocelyn gave up on getting her driver’s license because she backed Uncle Leonard’s car into a tree while he was teaching her how to parallel-park. It has been like that with everything—Aunt Jocelyn folds whenever she gets agitated. To keep herself from getting agitated, she must take pills that Uncle Leonard used to mark off on an index card taped to the refrigerator. He used to do everything for her—drive her to mass every morning, schedule doctors’ appointments, bring her to the grocery store, buy clothes for her, choose books from the library so she’d be content while he ran the hotel and gift shop.

Back when the starch queen was pregnant with Lenny, Aunt Jocelyn talked about wanting a baby too, but Uncle Leonard reminded her, “Not in your condition.” To appease her, he planted a rose garden on the semicircle of lawn in front of his hotel, prize-winning varieties of hybrid tea roses that he ordered from a catalogue —selecting them not for their colors but because their names attracted him: Command Performance, Sterling Silver, King’s Ransom, Golden Gate, Apollo, Century Two, Royal Highness, Texas Centennial.

But Aunt Jocelyn never even watered the roses. He was the one who would fertilize them in March and September; spray against rust and mildew, aphids and spider mites; cut off their weak branches in the fall and prune the strong canes by a third; cover them with pine needles for the winter.

His uncle’s death has given Lenny an acceptable excuse to leave the seminary for a while to help Aunt Jocelyn get the hotel ready for sale. Lenny has some doubts about being in the seminary; for some time now he has felt that, if only he could get a few months away from there, he might figure things out. What he thought he wanted was much clearer to him before he entered the order, and in the four years since, he’s been trying to get back to it—that undefinable sense of one source.

Faith has become complicated: it has moved from his heart into his head, where it abides, fed by scriptures and prayers. But his heart keeps forgetting, and he no longer feels the certainty of faith that belonged to him as a boy.

Lenny has confided this to only two people—carefully to his adviser, Father Richard Bailey, and far more openly to his best friend, Fred Fate. Fred is two days older than Lenny and entered the seminary—so he’ll tell you—“because then everyone will have to call me Father Fate.” But you can see Fred’s faith in his walk, hear it in his laughter. In comparison, Lenny’s faith is puny. He feels constricted by his black clothes, yearns for canary yellow and a shade of orange so intense it’s vulgar, for lush green and the kind of blue you can climb into.

The morning of Leonard’s funeral, Fred checks out a monkmo-bile—his name for any one of the long, well-maintained cars in the Jesuit garage —and meets Lenny at the starch queen’s house for breakfast. Aunt Jocelyn already sits at the table, hands folded on her chiffon skirt. Her cousin, Bill, has brought her. Lenny is not used to seeing his aunt in black. Most of her clothes are white, and with her pallid complexion —“indoor skin,” the starch sisters call it—she usually looks like the overexposed photo of a lady missionary. But the black fabric makes her skin look even more faded. As Lenny reaches for his aunt’s hands and kisses her on both cheeks, he wishes he could sketch her: she has the kind of face that comes at you in eyes, all eyes.

The starch queen’s best friend from high school, Cheryl Albott, arrives with two tablecloths and stacks of matching cloth napkins that still have the manufacturer’s stickers on them. Cheryl, who works in the customer-service department at Sears, has a front row opera subscription together with the starch queen. For decades, the two have attended every opening night in Portland, and for decades Cheryl has given the starch queen refunds for fancy outfits that she buys to wear at the opera or other special occasions and brings back a day or two later.

Ever since Lenny became a Jesuit, Cheryl has looked at him with reverence and called him “Father,” though Lenny has explained to her that he’s a brother, and that brothers—though they take vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience just like Fathers—do not administer the sacraments or give absolution.

Cheryl’s arrival makes Lenny notice his mother’s dark tailored suit with the lace collar. “New?” he inquires, though he doesn’t really want to know.

The starch queen fondles her lapel, winks at Cheryl. “Only the best for Leonard’s funeral.”

At the grave site, Lenny holds Aunt Jocelyn’s elbow. She is younger than the starch queen, yet she can barely walk alone and stumbles frequently. Her cousin tells Lenny that Aunt Joce-lyn can’t prepare meals for herself, that she refuses to move out of the hotel although her side of the family has found a safe place for her to live.

“It’s run by the nuns. Your aunt could go to mass every day. You know how important mass is to her.”

“We don’t have to rush her.”

“She’s not fit to live alone. She doesn’t even use the phone.”

“I’ll look after her while I work on the hotel.”

“And how long will that be?”

After the funeral, when the starch queen tries to pile seconds on Fred’s plate, he diverts her by asking, “Did you know that Lenny hardly eats at the seminary? Don’t you think he’s getting awfully thin?”

The serving spoon with manicotti still in motion, the starch queen changes its course from Fred to Lenny, who mouths a silent fuck-you-very-much across the table to his friend.

“… working too hard,” Fred goes on. “Always running around. Looking peaked. Don’t you think so?”

Cheryl from the refund department gets that bless-me-Father look in her eyes, and the manicotti on Lenny’s plate is joined by a chunk of oily garlic bread.

But Lenny gets even when Fred is ready to leave. “Father Fate is crazy about your cooking,” he tells the starch sisters. “You should hear him. He’s always raving about you.”

Promptly, the starch sisters gather by the counter to wrap leftover lasagna, eggplant parmigiana, and poppyseed strudel for Father Fate, stacking everything in a shopping bag for him to take back with him.

“I can’t possibly eat all this,” Fred groans.

But Lenny urges the starch sisters on. “Father Fate is always so modest.”

“You’ll get hungry tonight,” the starch queen promises Fred. “You can share it with the other Fathers,” Cheryl says.

Wrought-iron balconies, too narrow for anyone to stand on, decorate the façade of Uncle Leonard’s hotel on N.E. Sandy Boulevard. Roses, the size of grapefruits, cover the slope in front, and the gift shop is crammed full of religious pictures and enough statues to outfit four cathedrals. It’s only a few blocks from the Grotto —Sanctuary of Our Sorrowful Mother—where visitors like to ride the huge elevator up a sheer cliff and walk the scenic pathway lined with the Mysteries of the Rosary.

During the year of Uncle Leonard’s chemotherapy, the hotel has grown shabby despite the efforts of Mr. Wolbergsen, the handyman, who moved to his sister’s in Walla Walla when Uncle Leonard closed the hotel three months before his death.

After Aunt Jocelyn goes to sleep, Lenny wanders through the rooms—all identical, with pale-gray walls, faded curtains, and a single painting above the dresser, usually of either Mary or Jesus with a liver-colored heart weeping through a gap in the tunic. Lenny settles himself in the room closest to his aunt’s apartment in case she needs help during the night, but when he wakes up, it’s already eight and she’s in the kitchen

, dressed for mass, stirring a concoction of lard and sunflower seeds on the gas stove.

He feels queasy. “I’ll eat later,” he says.

When he drives her to church in Uncle Leonard’s old station wagon, she sits stiffly next to him, handbag clutched to her chest, eyes vacant. During mass, she keeps frowning and rubbing one finger up and down the ridges as if to erase them. On the way home, Lenny stops with her at the hardware store and buys ten gallons of pale-gray interior latex while she lingers above the paint charts, pointing to bright pinks and reds. She won’t leave until he buys a quart of fuchsia.

At the hotel, she scoops the cooled lard and seeds into a pie tin and sets it out on the windowsill.

“Oh, it’s for the birds,” Lenny says.

She shields her eyes. Peers at him.

After he fries eggs and butters her toast, he begins with the renovation, starting in the last room down the hall. Soon, his eyes ache from the relentless gray, and his arms feel heavy when he raises the brush. He wishes he could accept everything about the Jesuits. Or nothing. While Fred chooses what he believes, Lenny feels uneasy in the middle. Yet, whenever he pictures himself leaving the order, he gets sweaty and afraid that his faith is not strong enough to stand on its own, that he needs the frame of the church as much as his uncle needed the props of religious statues and holy cards.

There is something about hard work and bone-aching tiredness that appeals to him, because, gradually, it blots his doubts. Specks of gray settle in his nostrils, his eyebrows, in the fine hairs on his arms. He swears he’s breathing paint.

Late afternoon, when he showers, he uses up four tiny cakes of hotel soap. Ready to cook dinner for his aunt and himself, he hobbles into the kitchen and finds Aunt Jocelyn sitting at the table, a can of tuna in front of her. He gets the opener, mixes the fish with mayonnaise, onion curls, and celery seeds. In the cupboard he finds a jar of pimentos and dices them, sprinkling them across the tuna salad.

Ursula Hegi the Burgdorf Cycle Boxed Set

Ursula Hegi the Burgdorf Cycle Boxed Set The Worst Thing I've Done

The Worst Thing I've Done Stones From the River

Stones From the River Hotel of the Saints

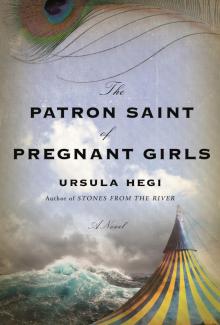

Hotel of the Saints The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls

The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls