- Home

- Ursula Hegi

The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls Page 11

The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls Read online

Page 11

“Today,” she says, “we must eat Kuchen first. Then stew.”

Silvio fingers the edge of the shawl and nods. “I’m glad it’s yours now.”

“Thank you.”

“We’ve been planning to give it to you.”

“Did your mother weave it?”

“When she was pregnant with me.”

Luzia The Clown kisses my baby’s lips and smiles. “God, how I want one of those.”

She never smiles during performances and gets our audiences to laugh at her melancholy as she plods through the sawdust on floppy shoes that are longer than her legs. As a child, she was a good gymnast. At fifteen, she attached herself to the Ludwig Zirkus with visions of being an acrobat. For years she kept herself reed-thin, held herself in, then figured out she wanted acrobatics, not famine. That’s when she reinvented herself and became Luzia The Clown, zany and graceful and round. Beautiful as long as she personified melancholy. But when she smiles, she looks wholesome. Ordinary.

“Gut?” asks Cook from the end of the wagon, where she’s rattling pans on the iron stove. The bed is at the opposite end, curtained off, built into the width of their wagon.

Her husband dabs whipped cream from his lumpy chin. “Divine.” He kisses his fingertips, opens them toward Cook, a pale beauty as long as she covers her mouth with her wrist when she speaks, to hide her worn teeth.

“So … I heard of a trapeze artist at a Zirkus near Bremen who calls himself—”

“Sabine may not want to know that,” Herr Ludwig interrupts.

“—The Fantastic Ferdinand.”

I lay down my fork, queasy with old lust.

They’re watching me, worried.

I let the silence sit until I can trust myself to speak. “Why not The Wonderful Waldemar?”

Nervous laughs.

“Close enough.”

“How about The Cowardly Cornelius!”

“I’m sorry I started this.”

“Cheating,” I say.

“Cheating what?”

“I like The Cheating Cornelius.”

“The man or his name?”

“Sabine likes the name—not that man.”

“Not that man.”

“I got a name that fits him just right. The Thoughtless Theodor!”

“The Lying Leonard!”

I laugh aloud.

“The Lying Leonard will sell you his lies as miracles in a jar with—”

“Meine Damen und Herren…” Silvio Ludwig leaps on the table and crosses his heart. Ladies and gentlemen. “It gives me inexhaustible pride and unfounded delight to introduce to you The Lying and Cheating and Cowardly Cornelius…”

At the long table, my tiny daughter travels from one nest of arms to the next, while we outdo one another with bogus names for her father, making this funny and scandalous. And we’re doing it, we’re succeeding. I laugh aloud. Everyone wants to hold Heike, and my body feels cold where before she was warm against me.

* * *

I borrow the death of Pia Ludwig and make it fit The Sensational Sebastian, the sort of death I dreaded while I loved him and couldn’t imagine a life without him. I embroider his fall from the trapeze, make sawdust rise around him and then drift down. Yellow flecks land in the luscious dip of his throat. Or on his eyelashes.

And yet. And yet, some nights I evoke The Sensational Sebastian: the tops of his feet pressing up hard against my soles, his palms flat against the top of my head, containing me within the borders of his body as only a tall man can.

* * *

Heike sleeping.

Heike laughing.

Heike eating.

Whatever she feels, I feel.

Even when I’m sewing or ironing, I’m aware of her every breath.

The Ludwig Zirkus becomes our family. Luzia cuts and paints paper butterflies that she hangs from our ceiling to entertain Heike who lies on her back, kicking and reaching for the colors and shapes. The runt Nowack buys her a frog puppet, green felt. The giant Nowack knits a blanket for her. The Twenty-Four-Hour Man brings a wooden duck with wheels. Herr Ludwig buys her a wicker baby carriage and a soft brush. She falls asleep in his arms whenever he brushes her hair.

I write a letter to my parents: Your granddaughter is strong-willed and lovely and funny. Tear the letter apart. Write another. And tear that apart too. Whatever I write is not enough.

“Once I sew a good mourning dress,” I tell Luzia, “I’ll take Heike and visit my parents.”

“An elegant mourning dress,” Luzia suggests.

She comes over a lot more since Heike’s birth, holds her and sings to her; we’ve become closer this month than the entire year I’ve been here. In trunks with fabric remnants we find pieces of silk in yellow and in green. When we boil black dye and soak them, they don’t match. I’m disappointed.

But Luzia is excited. “You can do something stylish and daring with two shades of black.”

“I don’t feel daring.”

While she covers twenty-four tiny buttons with the lighter black silk, I design a dress similar to one I made at the Becker Mode Atelier.

“Stunning,” Luzia says when I model the dress for her.

* * *

I’ve been away for nearly a year when I visit Rodenäs, Heike in my arms. I’m elegant in black, a young widow grieving. So much compassion and joy from my parents who welcome Heike and me with a celebration dinner; former classmates are envious of my freedom; and men gape at me with a frank hunger never aimed at me before.

My mother takes me aside. “Men think once you’ve done it, you want it all the time. Blessed fruit of your womb and so on and so on.”

I stare at my pious and proper mother who perhaps was not all that pious and proper, and we both clasp our palms across our mouths so that others won’t hear us giggle.

For all of them, I let The Sensational Sebastian live just long enough to breathe his undying devotion to me. What remains the same in all versions is how my Krämpfe—cramps—begin while I kneel by my dying husband in the arena, and how, that very night, I birth our child. Again and again I kill The Sensational Sebastian. A shy pleasure, some days. But mostly the need to prune the offshoots of that love.

* * *

Herr Ludwig lends me a green leather book, Arabische Nächte. “It belonged to my Pia. She read these stories to Silvio. Every night. I listened too.” His face transforms—tender and sad. “Stories that Scheherazade told King Schariar to save her sister and herself and countless other virgins from his massacre. Eventually, Scheherazade taught him to be compassionate.”

From Silvio I know how turbulent his parents’ marriage was. Accusations and promises. Elaborate drama every day of Silvio’s childhood.

Herr Ludwig traces the embossed design on the book’s cover. “You may borrow it, Sabine. It’s the best thing I own.”

Is he so fascinated by Scheherazade because, unlike his wife, she lived on?

“The one story I don’t believe,” he says, “is the central one that makes all other stories possible. How a woman so courageous and resourceful can marry such a beast.” He gives me a meaningful glance. “I want stability for Heike.”

“So do I.”

“Stability for Heike and you … and for my son.”

So worldly he is, understands that his son likes men. Yet, is hoping for a cure? Me?

“Silvio is amazing with Heike,” he reminds me at least once a week. “Have you noticed?”

To Silvio he says, “You’ll make a great father.”

“You two go out and dance,” he tells Silvio and me. “Dance is the poetry your feet make. That’s what the poet John Dryden said two centuries ago. I’ll stay with Heike.”

Silvio and I are both twenty-four, and we like to dance and eat and talk about men. Some nights he leaves a pub with some stranger. But he never brings him home. How terrible it must be to hide who you are.

22

Luzia The Clown and the Whirling Nowack Cousins

&n

bsp; Our audiences love the Nowacks who amaze you by toppling your expectations. One Nowack is much taller, wider in the chest; the short one barely weighs half as much but has the strongest little legs. Their size difference is extreme, and when they run into the arena on bare feet, you point and shout. No matter how often you’ve seen the performance, you still expect the giant to juggle the runt. The act starts as usual: the short Nowack walks to the center of the arena, lowers himself onto a wide carpet pillow that makes him look even smaller, and lies back, knees bent; except this time he does not raise his legs but lets his knees drop open, turns his face toward Silvio who stands near the curtain, fastens his eyes on Silvio who crosses his arms across his chest, recrosses them, face crimson.

Herr Ludwig flicks his ringmaster whip into the air, twice, before the short Nowack snaps his knees shut and raises his legs, flexes his bare feet so that his soles are parallel to the ground. When the tall Nowack runs toward him, the short Nowack catches him with his soles and launches him into the air, whirls him head to toe, then side to side, a blizzard of motion while the short Nowack lies without motion, except for his soles.

“You keep your eyes on your partner,” Herr Ludwig admonishes him after the performance. “To not do that is dangerous. For him and everyone.”

* * *

Late one evening Silvio and I meet at a rathskeller with Luzia The Clown and The Whirling Nowack Cousins. When Luzia orders Bratkartoffeln mit Speck—fried potatoes with bacon—the waiter says it’s too late to prepare warm food.

She scowls. “Nothing will come between me and my Bratkartoffeln.”

“I’ll get you whatever you desire.” The runt winks at her and slips the waiter a ticket. “I used to work for a famous Zirkus, very prestigious—”

“You are embarrassing yourself,” says the giant cousin, voice low as if it came from his toes.

“—and I got them whatever they desired … Not some mud show like this.”

“Tell me more about your prestigious Zirkus.” Silvio leans toward him. Sets his hook. He has an instinct for ausfragen—asking—until nothing is left.

“I have a fiancée,” the waiter hints.

“Congratulations.” The runt sighs and tosses him another ticket, plants his elbows on the table, stretches his jaw forward till his flushed face is a hand’s width from Silvio’s. “This prestigious Zirkus had a dozen big cats and a dozen teams of horses and a dozen—”

“I’m sure those dozens and dozens are more prestigious than our animals.”

“You want any? I’m good at bartering. They have so many animals … I can go to them.”

“What for?”

“For you. Barter.” The runt’s voice turns lazy. “If that’s what you want.”

Silvio shakes his head, dazed. Usually he’s good at spotting an upcoming crisis, takes it out of its wild spin, freezes it, till he can resolve it. But not now. “Barter what for what?”

“For what you want to … offer.”

As Silvio blushes a deeper crimson, I see the heat between those two that I’ve mistaken for hostility.

“Labor,” the runt says. “I’m talking about physical labor.”

Luzia and I glance at each other, and I bite my lip to keep from laughing. She coughs into her fist.

“Whose labor?” Silvio demands.

“Not mine,” says Luzia The Clown.

“Macht Platz!” The waiter yells at us to clear space as he advances with Luzia’s Bratkartoffeln mit Speck.

“Admit it,” I say to Silvio.

He flinches. “Admit what?”

I let him wait. “That you two enjoy fighting.”

“Only about Bratkartoffeln,” the runt explains. “Silvio is mad I didn’t get him any.”

Luzia perches her delicate hand on the giant’s broad wrist, and it’s then that her sadness merges with the giant’s sadness, igniting more bliss than two people can possibly generate. He closes his long eyelids because what he sees is for him alone: Luzia on her bed in his arms, toes just up to his thighs, lips against his throat. A low rumble of his laugh. “You are a beautiful man,” Luzia murmurs, and it doesn’t matter if her voice comes from his longings or from their future.

You are a beautiful man. It’s in the giant’s step when he walks with her from the restaurant; it’s in the way he extends his elbow in case Luzia wants to walk arm in arm. But before she can, the runt slows in front of her so that she has to bump into him.

“I didn’t mean to push you,” she tells the runt.

“Yes, you did. The imprint of your bosom is on my back.”

“Don’t be an Idiot.” Silvio Ludwig butts his shoulder against the runt’s.

Luzia laughs. “I hope that imprint lasts you a lifetime. Because that’s all you’ll get.”

A lifetime. That’s what Luzia and the giant Nowack promise one another—a lifetime of joy and of sadness and of trust, shared. I sew the wedding garments: Luzia wants a gown she can dye and wear as a costume in the arena; the giant Nowack asks for a blue tuxedo. “Midnight-blue.”

* * *

“My father’s snoring is getting worse,” Silvio Ludwig mentions the morning after their wedding at breakfast.

“I didn’t sleep all night,” Silvio Ludwig mentions the following day at dinner.

“I’m exhausted,” Silvio Ludwig mentions during rehearsal.

“I don’t want to keep you awake,” his father says.

“You don’t snore on purpose, Vater.”

Every day Silvio bemoans his lack of sleep, the circles around his eyes his proof. But Luzia has a different diagnosis. “Lovesickness.” For weeks, Silvio goes on like this, until his father asks why he doesn’t use the empty bed in The Whirling Nowacks’ wagon. We still call it that though the giant Nowack lives in Luzia’s wagon.

“I haven’t thought of that,” Silvio says.

When I wink at him, he blushes. A terrible liar.

Hans-Jürgen pretends indifference. Shrugs. “No one uses Oliver’s bed.”

“Then Silvio should move in with you,” Herr Ludwig says.

“It’s your Zirkus…”

“Would you mind if Silvio—”

“Your Zirkus.”

“Oliver’s bed is bumpy,” Silvio will complain to his father, to anyone who’ll listen, even Heike.

Luzia and I are sure he doesn’t sleep in Oliver’s bed but is building evidence if his father were to ask.

“Too much evidence,” Luzia warns him.

“You can stack your dishonor against mine,” I tell him. “A lover you can keep a secret; a child you can’t.”

23

Tell Me the Story of How My Vati Could Fly

I marvel at my daughter’s strong little body.

Marvel at her first step.

Her first word: Mutti.

When she laughs her belly quivers; and when she gets upset she bawls like a lost calf. I brace myself. Try to hold the middle. While I stitch, she sits on the floor by my sewing box, plays with the shiniest buttons, pushes them toward stripes of sun that lie on the floor. Heike moves with the sun.

From Herr Ludwig she learns to count by lining up her buttons and clapping her chubby hands: Eins zwei drei vier eins zwei drei vier … She is learning so quickly. Faster and faster she gets to twelve. Where she stops. And starts with one again.

A fidgety sleeper, she’ll shrug off her covers. Always warm where I’m chilly. Just before dawn she’ll burrow into bottomless sleep and fight awakening. Every morning a new battle with the light; eventually, I let her sleep. No matter what time she climbs out of bed, she’s groggy.

* * *

Over the next years I learn how time and facts can be manipulated; whenever Heike asks about her father, I concoct tales to shield her from the truth that he abandoned us. Her favorite tale is of him flying.

“Tell me the story of how my Vati could fly.”

“When your father flew through the air, every woman in the audience believed he was looking at her al

one.”

“But then he fell.”

“True.”

“And then he died.”

“Now he’s in a beautiful cemetery.”

“On a hill.”

“True.”

“With statues.”

“Big statues, ja.”

“Apple trees.”

“True.” I beam at her.

“I saw how he fell.”

“You weren’t born yet, Heike.”

“I saw him.”

It unnerves me how she absorbs my lies as memories of her own—his fall, his death, yellow sawdust on his face.

* * *

Along the way I befriend women. If you want friends, Luzia has told me, you cannot wait because soon you’ll be on the road again. “You have to charm them with your frankness, your humor, your praise of whatever you can genuinely praise about them.”

“I already have you.”

“You do. But you need more friends.”

“Sometimes I shock people,” I tell Luzia, hoping she’ll say I don’t shock her.

But she nods.

“I was shy as a girl until I found I’m not afraid to say what I think. You think I shock people?”

“Ja.”

“Do I have to be more careful?”

“You like to shock people.”

I have to laugh. “Yes.”

“Why give that up? We’re never anywhere long enough for you to offend anyone.”

“I don’t want to push you away.”

“No chance.”

* * *

For the third time in a week, Heike wants the story about the frozen-together dogs.

“One cold day my Vati saved two dogs.”

“True.”

“It was very, very cold.”

“Ja. He ran from our wagon into the deep…” I wait for her to finish my sentence.

“… snow and he chased the boys away because they … because—”

Ursula Hegi the Burgdorf Cycle Boxed Set

Ursula Hegi the Burgdorf Cycle Boxed Set The Worst Thing I've Done

The Worst Thing I've Done Stones From the River

Stones From the River Hotel of the Saints

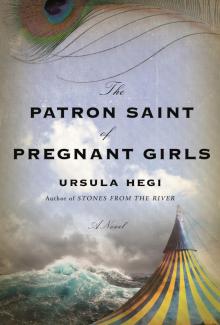

Hotel of the Saints The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls

The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls