- Home

- Ursula Hegi

The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls Page 13

The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls Read online

Page 13

“But—”

“I’ll carry Wilhelm. We’ll talk when we get back.”

25

In the Big Nursery

That night in the Big Nursery, Tilli lies awake in the alcove across from the beds of the sleeping children, four rows of six. As she tries to steady her breath—louder and faster than the breaths of these children—she longs to be an Old Woman. First Sabine will become an Old Woman. Then Lotte. And then Tilli will join that circle. And never be alone again and no one ever telling me to go away or stay because I’ll be the one who gets to say.

The first time she took Wilhelm to her breast, she made a promise to Lotte to steal Sister Franziska’s rosary, a silent promise that matters more than spoken words. She leans over the side of her bed, slides her handkerchief box from the satchel Sister Franziska has let her pack. In the dark she tiptoes past the little beds and down the stairs to the infirmary where she slips the rosary from the key of the medicine cabinet. In the kitchen she melts its amber beads in a jar set within a pot of boiling water. As she waits for the amber to soften, it releases the scent of childhood, of pine and salt. She pummels it into one sticky lump, cuts that into pear-shaped halves the size of her little finger, jiggles the moon clippings of Wilhelm’s fingernails from her handkerchief box, and presses them into the amber halves before she connects them again. With her hairpin she pokes an opening for a cord. Come light of morning, she sees the bubbles that have settled around the moons like halos.

* * *

The Big Nursery is much bigger than the Little Nursery. Three rooms: The sleeping room. The learning room. And between them the playing room with a big table where the children clamor to stick their fingers into the jam because Tilli did it first, one long finger to fish for the dark speck inside the jam. Not a fly but a bread crumb that looks like a fly but isn’t a fly because Tilli gets it out, more jam on her finger than needs to be.

She licks it. Makes her eyes go big.

“Me.”

“Jam.”

“Since you’ve finished your barley soup…” Barley soup with carrots and bits of apple that she carried up from the kitchen for her children.

“Me. Me.”

They lean across the table, try to climb on it.

Tilli holds the jar upside down to make it easy for their little fingers. So what if jam gets the table sticky? She wants to cheer them up. They shriek with delight that comes from the forbidden. Jam on their cheeks. Around their lips. The Sisters are shadows that fade for Tilli when she plays with the children, when their joy restores some of the warmth beneath her heart where her own girl slept till she was born and where Wilhelm lived until she was banished from the Little Nursery. She still sees him, but not enough.

“Fizzy!” the children cry.

“Ticklish!”

They point to her amulet where it lies against the dip of her throat, the shimmer of honey. She keeps it shiny by rubbing it with spit every day.

“The hair on my arm,” the children cry.

“Make it stand up, please.”

“My arm first.”

She slips off her amulet. As the children press against her, she sways the amber against their arms, and they giggle at the sparks. She loves her work with the big children far more than she thought she would when Sister Franziska banished her from the Little Nursery a month ago.

“Slivers of moon inside.” She kneels amid the children so they can see the pale slivers inside her amulet.

“How did you get them, Fräulein Tilli?”

“From the sky. They’re magical.”

Magical. The children sigh with wonder.

* * *

As soon as Lotte believes her husband will never come home, she has a dream about waking up to the smell of gravy, rich and brown, and feels a pulling in her groin, a heat—

—and running downstairs barefoot in her nightgown wondering if you can smell anything while sleeping and in her kitchen Kalle cooks his Sunday gravy, browns a fist-size chunk of meat with onions and bacon, and he doesn’t notice her though she stands behind him with her arms around him and her palms on his chest so hot his skin hot the air stirring he’s stirring—his miracle not loaves and fishes but gravy he can expand till he has plenty—and just before his gravy is about to burn he adds water, lets it hiss and boil and thicken, and again he stirs and browns until she smells his gravy on her skin and in the mist that surrounds her house and—

—dawn, then. And her house too cold to hold any smells, other than the smell of cold itself: stone and dampness and snow. Lotte shivers, tugs the bedding around her shoulders. Not Sunday. But a watery Tuesday in February. By late morning she’s outside with Wilhelm beneath a patchy-thin cover of clouds, hanging laundry on the line. He takes one cautious step, clutches a fold of her skirt. Yesterday he took his very first step away from her. Now he studies the ground as if considering his next step. Much of the snow has melted, softening earth into mud, but some snow clings to the bottoms of dried grasses, pockmarked where rain has pelted it. Above the darker stones the snow is gone.

Wilhelm takes another step. Tips his face to his mother, astonished by what he can do, beams at her.

“Look at you!” She laughs, sets her laundry basket on a flat stone, and squats, her arms one safe circle where he can walk. Another step—

* * *

—and it’s then that her husband rides into the yard on a stiff-legged zebra. Its back is damp. So are Kalle’s shoulders and hat. And he’s already wrong because he sees her smiling and has no idea it’s at Wilhelm, not at him, because he smiles at her.

“Please,” he says.

His presence intrudes on her longing for him when longing itself has become familiar. She wants to fly at him with her fists raised.

“Lotte,” he whispers.

Wilhelm teeters on his baby legs, and she tightens her arms around him, feels the edges of shells he’s crammed inside his pockets again, makes herself think of those shells, sees herself emptying the pockets before the wash. How many times have you turned your children’s pockets and socks to get at the stones and shells and sand? Sand is the hardest because it will hide for several washings in seams and in corners. Long after the wave you still find sand in the socks of your children.

Kalle slides off the zebra, his legs as stiff as the zebra’s, as though he’s been riding it every day of the six months he’s been gone.

“I have—” He clears his throat. “I have an idea.”

She won’t speak. Won’t make this easier for him, though her body is straining for him as if they had no betrayal or death between them.

“An idea for a trade,” Kalle says. Away from his family he has felt unmoored, floaty; has sketched his children the way he used to, the easy curve of Lotte around them before and after birth; but they no longer come together for him, are merely charcoal lines on paper that prove how much he has lost. So much easier to draw animals.

“The zebra can bring you income.” Kalle pats its mangy flank.

“I can raise colonies of moths in that fur and sell them.”

“That’s the Lotte I know.”

“You don’t know me.”

Wilhelm hides against Mutti’s leg, peers at the horse-with-stripes as it smiles, snorts, curls its lips, shows him long teeth. Wilhelm curls his own lips, shows his own teeth to horse-with-stripes.

“I want to help, Lotte, with the farm and—”

“There is no work for you.”

“You can rent the barn to the Ludwig Zirkus. I can bring a few sick animals, make them stronger here.” Three weeks ago he seized a moment of disagreement over killing this ancient zebra and offered to stable her on the farm his wife brought into the marriage. It gives him cause to stay without telling Lotte he wants to come home. And he doesn’t, or at least isn’t sure enough to let her know that he doesn’t know. “And maybe,” he adds, “next winter the entire Zirkus can winter over.”

“I’ve leased the farm to the sexton.”

“Old Nies

sen? Who drinks the piss of sheep?”

“The piss of goats.”

“Goats, then.”

“And he doesn’t drink it. He gets it through a syringe.”

“I don’t like another man doing my work.”

“Your work?” she asks, ablaze with anger.

26

Of Being Alone and Untouched

All Kalle sees is radiance, and for one insane moment he knows she has another man. He’s back in that panic of being alone and untouched like the day before Christmas when the others are leaving to visit their families, and he tries to keep that panic at bay by thinking of the jars of Lotte’s Hagebutten Marmalade on the shelves in the cellar, of the wild beach roses—pink blossoms early summer; scarlet fruits late summer—and he can taste it then, thick jam as sticky as honey with the flavor of summer, countless summers, a history of all summers with Lotte, and still the panic gets in and squats in his soul.

“I haven’t been touched,” he blurts. “By a woman.”

“Why are you telling me this?”

“I want you to know.”

“I don’t want to listen to this.” She covers Wilhelm’s ears with her palms and sees Kalle in the embrace of Sabine Florian who can have any man any age. A new jealousy, hers alone, and he has no right to it.

He doesn’t have words for this yearning that cannot start with Lotte, because he must ban her from his heart so totally that yearning can only steal in sideways—the length of a woman’s step, say, or the curve of a woman’s shoulder beneath a dress, or the turn of a woman’s neck—sparks of yearning that lead to Lotte. Ignite.

“Here you are, using a mangy zebra as an excuse to come back. Offering me a barnful of mangy animals.”

“It’s not like that. I want you to have that income.”

“I already have income.”

“From where?”

“The St. Margaret Home. I’m training to be a midwife.”

They trust you to bring children into life? He covers his mouth. Runs his palm across his mouth and chin. Stubble and sweat. She must be disgusted by him.

He asks, “Is the sexton treating you fairly?”

“Is that yours to ask?” It comes out harsh.

But he won’t let her push him away with her anger. If anything, he’ll fan it, keep it aflame, both of them guardians of her anger. Safer than talking about their children.

“He is treating me fairly.”

“Good.”

“You cannot be here just because of me. You don’t even look at your son.” She lifts Wilhelm up so his face floats in front of Kalle’s. “Wilhelm, this is your Vater.”

Vater. Not Vati.

The boy’s little arms splash the air as if swimming toward him and the zebra. His sleeves are too long. Bärbel’s coat.

Kalle shakes his hand. “Guten Tag, Wilhelm.”

Lotte turns Wilhelm toward herself, smiles at him. “Your feet are heavy. Sand in your socks again?” All while she’s aching to tell Kalle their other children are alive. Saddle him with that knowledge before he decides to bolt again.

Noch nicht. Not yet.

“Sand in your socks…” Kalle circles Wilhelm’s ankle with a thumb and finger.

* * *

Lotte leaves him standing under the gray sky by the barn. Wilhelm on her hip, she runs toward the St. Margaret Home. She’s not on duty, but she can’t be home with Kalle.

By the front door, Sister Sieglinde walks into her, and Lotte sweeps one arm forward, curtly, motions Sister into the vestibule.

But Sister stops. “What happened?”

“You go first. Please.” Lotte doesn’t like the chill in her voice.

Sister Sieglinde loves to talk, and if you don’t get away, you’ll have to listen once again to her rant about papal pomp. It started when Sister Sieglinde was Lotte’s teacher and visited the Vatican as a delegate of the Sisters. She was so appalled by the treasures in the Vatican’s museum—immense and obscene, squeezed from the most destitute of believers—that she thought of renouncing her vows. Instead she bought a filigreed rosary and two oranges blessed by Pope Pius IX. One orange she gave to the Pregnant Girls, the other to her third-grade students. The rosary she tried to give to other Sisters, but they didn’t want it either because its silver tracery snagged their skin. An instrument of penance, they called it.

“What happened to you, Lotte?” Sister Sieglinde asks again.

“I must go.”

“You look furious.”

Lotte adjusts Wilhelm’s weight on her hip and turns away.

She roams the corridors yet can’t settle herself. She’s in a funk. In a hatchet-wielding funk. If only she had a hatchet. But then what? Too much, even this. Too much of life and plans and birds and choices and now Kalle. Inside the chapel she slams the door so hard that candles flicker on the iron stand by the altar. She nods to herself, opens the door again, slams it harder. There! And again. In the last pew she hides out with Wilhelm. She hums to him. Hums while that crucified Jesus hangs above the altar as if to prove that he, too, was pushed from inside a woman.

27

The Mathematics of Loss. Of Desire

Before Lotte goes to bed, she sets out food for Kalle on the kitchen table that he takes to the barn and eats alone on the edge of his cot. Pea soup with ham bone. Goat stew. Potato pancakes.

He muddles along, trying to anchor himself in daily tasks. Near Lotte. For now. How he misses the everyday stories he and Lotte used to tell one another—about what they’ve seen and thought and tasted—looking forward to the telling because they know the other will want to listen. These are not stories you save to write in a letter: they’re insignificant to others and therefore all the more significant to you.

If I were to ask Lotte whose hand was in hers, she wouldn’t answer, wouldn’t tell me whose hand she let slip away when Wilhelm needed all of her. He’s been like that, the boy, from the day he was born.

Whose hand? he’ll insist, afraid she’ll send him away for asking.

I don’t remember.

Why did you let go of the others? Pushing at her with questions, feeling cruel. What right do I have after deserting her?

There was no time— For choice.

To console her he’ll say, If you had dropped Wilhelm and held on to the other three—then their weight, their combined weight, would have pulled you out with them, drowned you all, and I wouldn’t have any family—

But what he sees are his children torn from her hand—Bärbel Martin Hannelore—while she still holds on to the youngest.

The mathematics of loss. Of desire.

* * *

Second Tuesday after his return she waits for him, cheeks flushed. On the table a yellow wedge of Rodonkuchen on a good plate. To bake his favorite, Apfelkuchen, would mean Willkommen. His Lotte does not pretend.

When she motions for him to sit across from her, he’s sure she’ll ask him the question that has lived inside his fear.

Why did you desert us?

Because you would’ve sent me away—

She says, “I baked Rodonkuchen this morning.”

“Thank you.” He shows his appreciation by taking a bite of cake, an average bite, not big at all, but it clogs his mouth. He can’t swallow, coughs, face hot, feels the dead children inhabit his house.

Lotte gets him a cup of water. “Slow now.”

Still coughing, he gulps the water, maneuvers the lump of cake into his fist.

“Promise—” She hesitates.

“I promise.”

“You don’t even know what it is.”

“I can promise to listen.”

“Promise to believe me.”

“I swear I will.”

She hesitates. Then tells it like a riddle. “Small voice? Big laughter?”

And he gets it right. “Hannelore.” It hurts to say her name aloud, but he continues. “Her voice so quiet, but her laughter always the loudest.”

“You think it’s because sh

e is the oldest?”

“Could be,” he says cautiously and hides his fist with the lump of cake on his knees, then pushes it into a pocket.

“Or will her voice always be like that?”

Always? The skin at the edge of his hairline prickles. “I’m not blaming you, Lotte.”

“Because they’re alive.”

“What?”

She nods, keeps nodding, such joy in her face. “Hannelore and Martin and Bärbel.”

He groans. “Oh, Lotte…”

She presses two fingers across his lips. “They held on to one another. That’s how they made it to Rungholt.”

“And how do you know that?”

“From our children.” She raises her chin, challenging him.

“Who watches over them?”

“People. There.”

“Who plays with them? Tells them bedtime stories? All the things I used to do with them.”

“The people who teach them also watch over them. Like at the St. Margaret Home.”

“Nuns, you mean?”

“Not nuns. A family. People on Rungholt have found a way to adapt.”

“Adapt? Like salamanders? Like in a cave or a grotto or some … some Garden of Eden?”

“You— You are a Doubting Thomas. It takes courage to believe, and you want to touch them before you believe.”

Oh, to touch you—

“But you can only touch them afterward. The first time you believe, however briefly, it grows. Like healing after an injury … like when you broke your arm fishing. In the beginning you feel the pain constantly, but there’ll come a day when you can’t feel it for a minute. Soon, you notice you’ve been without pain for half an hour. Then half a day.”

* * *

False starts.

Misunderstandings.

Clashes between reason and hope.

He comes to her along the ocean side of the dike, leaves the cot in the barn where he sleeps, and walks to her bed that also used to be his. Here in the dark room beneath the pitched roof, they lie side by side without touching and whisper about their children away on Rungholt.

Ursula Hegi the Burgdorf Cycle Boxed Set

Ursula Hegi the Burgdorf Cycle Boxed Set The Worst Thing I've Done

The Worst Thing I've Done Stones From the River

Stones From the River Hotel of the Saints

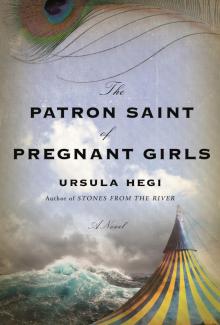

Hotel of the Saints The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls

The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls