- Home

- Ursula Hegi

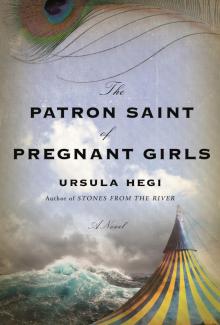

The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls Page 17

The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls Read online

Page 17

Kalle scans the dark band of horizon and beyond where their children live. Let them be on Rungholt, then. At least he and Lotte are in this world together where planning to be with their children lifts the pain. But you must move swiftly before reason can stop you.

“Just a few hours by rowboat,” he says.

* * *

That night she pulls Kalle beyond his edge of reason. Turns on her side, knees and forehead against his while winds bear down on the house her grandparents built against the dike. He presses his forehead against hers, shifts his knees toward hers. The center between them is empty, shaped like a heart. Oh—to have you again. She strokes his sternum, opens herself to him, body and soul, an instinct more urgent than making a child: this here is a frantic summoning of the three already born, a frenzy of tearing and tasting and biting they would have been shocked to imagine before, all for the sake of reaching their children in this world where wanting to believe becomes believing. Falling then—into faith, into absolution—and he plummets with her toward Rungholt, feels the heft of his children as he clutches them into his arms. Alive and we’re not to blame. No stranger than miracles we’ve grown up with: Jesus strolls on water; the crippled rise; a dragon spits up a saint; priests drink Jesus’s blood; the dead come to life …

He will bring them home: Bärbel, quirky and giggly, no eyes for anyone else when her Vati is there; Hannelore with her remarkable questions, certain her Vati will answer them; Martin, smart and moody, who may become a quarrelsome man if not guided by his Vati. And guide him Kalle will. Guide them all with patience and kindness.

* * *

At the school museum Lotte and Kalle examine journals and letters, unroll a brittle vellum map from the seventeenth century and weigh down the yellowed edges with books. Over centuries, the museum has grown, curated by the Sister who has her office in the museum where she’s allowed to sit in the embroidered armchair or rest on the sofa, prepare for classes at the fourteenth-century marble table, surrounded by seascapes and framed documents.

They find letters tucked into pages of church records.

A warning from a survivor:

Stay far from Rungholt during slack tide just before the current reverses.

Be vigilant. I nearly drowned.

A priest advocates in the 1683 church records:

If you see Rungholt, you must turn back, or the vortex will drag you down.

The beekeeper’s great-aunts write about fishing one spring when the island rose up in front of them:

We were lucky the water pushed our dory away. When Rungholt sank again, we were already beyond the outer ripples.

Lotte and Kalle discover circled entries that span two centuries:

I am preparing to leave for Rungholt.

We’ll wait for the first high tide after the black sun of spring.

My ancestors own a brick kiln on Rungholt.

A shipyard.

A farm.

The same annotation with each circle:

Nicht zurückgekommen. Did not return.

What Kalle and Lotte take from those entries is this: you must row out and wait directly above Rungholt; you must be prepared for that brief lull of slack tide when the island will rise—earth and structures—and lift your boat, allow you to enter and seize your children.

“It has to be next spring,” she says.

“That’s the soonest. Yes.”

They resolve to listen more closely to stories that have always been there of people who rowed out and witnessed Rungholt rise from the sea.

“I’ll prepare in the meantime.”

“But after that—how do we bring them back home?” Kalle asks.

“We don’t have to figure out the how. Not yet.”

35

I Know I’m Bossy

Heike screams when we tell her she cannot leave with the Zirkus, whips her hair from one side to the other as if shaking out water, brief flashes of face as she hides from us, from herself. Oh, Heike.

The beekeeper steps back.

But I walk into her, brace her with the momentum of my body, her head against my shoulder, until she quiets in my arms. “Oh, Heike.”

In the morning she’s gone. We search all over Nordstrand.

“I held her back,” I tell the beekeeper.

“You held her safe.”

“She wanted to fly at the trapeze since she was a small girl, but I insisted she become a musician.”

“You encouraged her to be a musician.”

“So much of raising her has been like that. Encouraging and insisting without telling her she’s not like other girls.”

“A secret between you.”

“That part of it. Yes. But there’s so much more, her joy, her—”

“When she is joyful. But today—” He pulls up his shoulders. “That was horrible, seeing her like that.”

“I’m sorry.”

He waits.

“I’m sorry I didn’t tell you about her rages before.”

“What else should I know?”

“It doesn’t happen very often.”

“That’s not what I asked you, Sabine.”

* * *

I’m not surprised when Silvio rides back with her on his horse.

“You and I can go,” she whispers to me.

“We live on Nordstrand now. Remember?”

“I want to live with you and the Zirkus.”

“You have a husband now.”

Heike groans. “I don’t want a husband.”

When she runs away again, the beekeeper and I know where to search and follow the Zirkus route in the carriage. But Heike refuses to return with us. First I try with words—I always do with her. When I pull her toward the carriage, she throws herself on the ground and shrieks.

“I cannot force her,” the beekeeper says.

“You don’t have to,” I tell him.

“I won’t force her to come home.”

Silvio lays a hand on the beekeeper’s shoulder. “Give her a few days with us.”

* * *

Heike doesn’t return the following day. Or the day after. Instead Tilli comes to our door and offers to keep Heike from running away. Before we can say a word, she thrusts an embossed certificate at us that qualifies her to work as a Kindermädchen—nursemaid.

“Sister Hildegunde says she’ll give you her personal recommendation.”

“Heike is not a child,” the beekeeper says.

“I know, but—”

“Thank you, Tilli,” I interrupt, “but Heike can wash herself and feed herself and—”

“But I can keep her safe. Make her want to stay at home.”

“How would you do that?” The beekeeper watches her closely.

“I’ll find ways to make her want to stay. Maybe I’ll start by playing Zirkus with her. Take her on long hikes until she’s too tired to run away. Let her help with the zebra and the other Zirkus animals.”

We talk. And keep talking long after Tilli has left to get her belongings from the St. Margaret Home.

“That girl needs a family,” the beekeeper says.

“That girl wants Lotte’s family. Lotte lets her visit a lot but not move in.”

“And now she’ll live next door to her.”

But when I tell Lotte, she says it’s a brilliant idea. “A very brilliant idea, Sabine.”

“This close to your house?”

“She and Heike will be good for each other.”

“Tilli adores you.”

“I’m in her way. It’s all about Wilhelm.”

“It may have been at first, but I see how Tilli looks at you.”

* * *

Four days later when Silvio brings Heike home, she won’t look at us. I try to embrace her, but she steps aside.

“Heike?” The beekeeper smiles at her. “We have a surprise for you.”

“What?” she snaps.

“The surprise is in your room.”

She shrugs.

&nbs

p; “A surprise?” Silvio raises his eyebrows. “Can I go and look?”

“I don’t know,” says the beekeeper. “You’ll have to ask Heike.”

She grips Silvio’s wrist. “We’ll look together.”

We follow them up the stairs. When Heike opens her door, Tilli pulls her inside.

“Where’s my surprise?”

Tilli points at herself and curtsies.

Heike points at herself and curtsies. “What are you doing in my room, Tilli?”

“That’s where I sleep when I live in your house.”

“No, you don’t live in my house.”

“Yes, I do.”

“You’re bossy.”

“I know I’m bossy.”

“Were you bossy when you were a little girl?”

“Ja.”

“Did you have sisters or brothers to boss around?”

One breath we are, Alfred, not knowing where it leads … but a given, natural … we no longer have that—

“Tilli!”

—don’t think about him don’t—

“I asked if you have sisters or brothers.”

“Only chickens and cows to boss around.”

“Do they listen to you?”

“Oh ja.”

“Where is your family?”

“… a fire…”

“My Vati is dead too. He could fly.”

“Fly where?”

“Everywhere. He flew away away from the trapeze the day I was born. But then he crashed.”

Tilli asks, “What side of the bed do you want?”

“My side,” says Heike.

* * *

“There’s a painting I must show you.”

I take Silvio to the St. Margaret Home where several of Sister Hildegunde’s paintings are exhibited in the lobby along with tapestries and paintings by students and Sisters. I don’t have to point Silvio toward the one called After the Zirkus because he’s already approaching the canvas of a stark Nordstrand landscape that holds the glitter and hum of the Zirkus, superimposed in fine layers, long after the Zirkus has left. Such a painting, Silvio understands, will pull you inside, make you sweat because you cannot imagine the painting in someone else’s house; make you decide to buy it before anyone else can.

I motion to him but he rushes toward a Sister who’s cleaning the birdcage and tells her he wants to buy After the Zirkus.

“It’s already sold,” she says and points at me.

He wheels toward me, scowling.

“We bought it—”

He slices his hand through the air, dismissing my words.

“—for you after Heike ran away again. We knew you’d bring her back.”

* * *

Silvio hangs After the Zirkus above the foot-end of the bed he shares with Hans-Jürgen. After weeks of gazing at the painting before sleep and upon waking, he fathoms that Sister Hildegunde must have taken a fragment of what he’s seen and dreamed and yearned for—all his life or for one moment—and reflected that in her painting, validating what Silvio has sensed, yet making it more significant so that, in memories-to-come, it will always be significant like that.

How did you know so much about me, Sister Hildegunde?

36

Our Own Hidden Wildness

Heike is exuberant now that Tilli lives with her. They roam the wetlands. Long steps, against the wind. Both strong. Heike lithe, Tilli solid. They take Wilhelm to the playground on the school hill. Push him and then each other high on the swings. Flying, legs pumping.

“Hold on now, Wilhelm.” Tilli has angel hair.

Heike pushes him higher, her hands on his back. “You like having wings?”

Wilhelm laughs.

They row out in Kalle’s dory, but Wilhelm is only allowed in the boat when his mother is with them. Patient and inventive, Tilli plays Zirkus with Heike and Wilhelm. Rewards them with food. They make the rounds of the neighborhood. At the St. Margaret Home Heike reads to the babies, pretend-reads, turns pages while Wilhelm makes singsong words of what he sees in the pictures.

Heike wants to please Tilli whose presence outshines the lure of the Ludwig Zirkus. The beekeeper is fascinated by their interactions. Heike looks to Tilli for information, which Tilli whispers to her so that Heike can present it as her own, believe it is her own. Emboldened, she’ll tell the beekeeper she loves mathematics, asks him to test her. Cheerfully she’ll call out some number, any number—eleven or twenty or five—and laugh when that’s incorrect. When Tilli corrects her, Heike asks him to test her again.

The beekeeper laughs. “You’re throwing into the dark.”

Moments like this he can love Heike, not as a wife who makes him wonder if this marriage should have been—a question he only allows himself in his loneliest hours—but love her as a stepdaughter who is crafty and funny and slow.

Most evenings she practices her cello for hours, and he listens, mesmerized.

“Your mother told me you are talented,” he says, “but I had no idea how talented.

“Would you like to give a concert?” he asks her.

“Can Tilli come to my concert?”

“Anyone you want to invite.”

“I’ll be there,” Tilli says.

* * *

I like doing the design and major sewing projects for the Zirkus that the Twenty-Four-Hour Man delivers once a month. The Ludwigs have hired a woman to help with cooking and small mending jobs.

Now that Lotte and I are neighbors, I bring to her all I’ve learned about friendship while on the road, try to charm her with candor, with praise, with the offer to design a dress for her. We walk along the shore and talk; sit by the Kachelofen—tile stove—and talk: about us, about Heike, about Wilhelm—but not about Lotte’s other children.

Not until I’m on my knees, pincushion on my wrist, adjusting the hem of the new dress while she stands on my sewing stool.

“That afternoon on the flats…” she starts.

That afternoon on the flats … I wish I could tell her how futile my fear for Heike felt when Lotte lost three children, healthy children—not like Heike. Too soon to tell her, I think. Not at all, I think.

“That afternoon you said you’ll do anything for me.”

“It’s what I felt.”

“Still?”

“Still.” I wait for more. Stick another pin through the fabric.

“So if I ask you something indiscreet—will you tell me?”

“Ask, then.”

“Kalle—” She looks embarrassed, angry. “Were you with Kalle?”

I sit back on my heels, pins between my front teeth. “No!”

“Ever?”

“How long have you—”

“Since the first time he left. About you or some woman.”

“Have you asked him?” I motion for her to turn to the right. “Not that far.”

“Like this?” One small step. “He says he hasn’t been touched.”

“I believe that.”

“Why should I?”

I stick in another pin. “I stuck Kalle with a needle once, no, twice. The first by accident, the second on purpose—that’s how furious I was. I didn’t want him to get away like that, leaving you with the loss of—”

“You still haven’t said why I should believe him.”

“Kalle isn’t…”

“Isn’t what, Sabine?”

“… awake. In that way.”

One corner of her mouth rides up. “With me he is.”

“Then I’m glad for you. For both of you.”

* * *

Whenever we go near our hives, Heike, Tilli, and I wear white hats with netting like the lady missionaries on the collection box in church, and we put on accents, the way German missionaries might talk in Africa. The St. Margaret Home is our best customer. The Girls love honey. So do the Sisters.

To hold him for my daughter, I pamper the beekeeper. Show Heike how to iron his shirts, twice, so that the collar feels like silk against his n

eck. Ask him about his favorite meals—“Entenbraten,” he says; “Weinsuppe; Zitronenkuchen”—and teach Heike how to roast a duck and simmer wine soup and bake lemon cake.

People claim I moved with my daughter into her marriage because that marriage would provide for me, too. But the beekeeper wants me here, grateful I look after Heike.

While dusting his workroom we find loose pages with puckered edges. Behind the bookshelves in Heike’s bedroom Tilli discovers stacks of overdue library books. Before I wash his clothes, I empty his pockets: coins, handkerchief, pieces of thin twine. If Tilli stays by her side, Heike finishes what she starts; left alone, she’ll try to get away, roam the meadows and dike with long strides. But now we have Tilli who always catches her and roams with her, brings her home with her hair tangled, face flushed, words tumbling with shifting clouds and sun, with thunderstorms and rainbows, with people and willows arching away from wind.

* * *

During Heike’s performance I sit with the beekeeper in the first row. We arrived early, amazed as the auditorium of the St. Margaret Home filled. Tilli is in the audience as promised, two rows behind us with Lotte and Wilhelm.

As Heike plays the cello, she pulls it against her body, into her body as if it were part of her, long arms reaching forward and around it. In her face every expression I’ve witnessed since her birth: first, of course, the coming into the void from the shelter of my womb, and spreading her arms wide; the enthusiasm of the small girl in motion, face tipped toward me, always, and the look-at-me, look-at-me; the sullen fifteen-year-old eating starling soup at the long table in The Last Supper, shoulders curved inward, face turned away from me.

And I see what I have not yet witnessed: Heike five years from now; Heike at my age, still child-like. I feel warm and take off Pia’s woven shawl, fold it across my knees, spellbound as a confidence comes into Heike, and she draws the bow across the strings. I know what her hair would feel like under my fingertips were I to brush it from her temples. Know how her wildness funnels into her music, only to claim her again—as it claims me; claims me again and again, though I can outdistance it—and I wonder how many in the audience recognize our own hidden wildness.

Ursula Hegi the Burgdorf Cycle Boxed Set

Ursula Hegi the Burgdorf Cycle Boxed Set The Worst Thing I've Done

The Worst Thing I've Done Stones From the River

Stones From the River Hotel of the Saints

Hotel of the Saints The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls

The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls