- Home

- Ursula Hegi

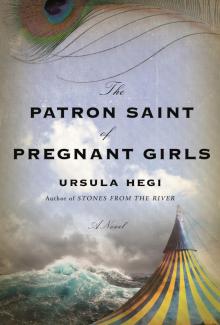

The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls Page 19

The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls Read online

Page 19

But Sister Konstanze understands her without words. Sits on the edge of the bed and strokes Sister Ida’s arm. To feel your skin despite the layers of our habits … stirs memories of so much more. Some nights Sister Konstanze slips from her cell, slips into the retirement wing, slips into Sister Ida’s bed. You’re accustomed to making one space fit two.

Sister Ida lets Wilhelm draw on her chalkboard. When it squeaks, she grimaces and taps her ear. Takes the chalk from him and shows him how to guide it gently across the chalkboard.

Wilhelm nods. Gets the chalk from her. Draws Verrückter Hund.

Sister grimaces and taps her ear.

Wilhelm grimaces and taps his ear. Pulls up his shoulders to make his hand lighter, draws a tree—no squeaking—next to the dog’s hind leg.

Sister smiles, holds out her hand for the chalk, writes words Wilhelm can’t read. “How I miss the certainty of waking next to you.”

But what Sister Konstanze reads aloud is this: “What I look forward to all year is that first delicious green of spring.”

“How I remember that…” Sister Ida writes. “With you.”

40

Their Own Patron Saint

Sister Franziska is the first to notice. With Lotte Jansen as midwife there have been no deaths—no infants, no mothers—going back to Hedda and her infant a year ago.

When Sister Franziska tells the other Sisters, they’re stunned.

“Of course,” they say, “but only in looking back.”

“I didn’t notice it till now.”

“No fresh graves since Lotte Jansen began to midwife.”

“Compensation for her terrible losses.”

“That’s why God is sparing her.”

“But for how long?”

“Until He has taken enough from her.”

“Who are we to question—”

“If we don’t, who will?”

As stories about the young midwife spread through the St. Margaret Home, the Girls come to think of her as their patron saint. They’re ready for a saint who soothes them, lightens their burden. What matters most is that the midwife will not judge them. The Girls believe it’s because she has done something far worse than they ever will. To give away one child to be adopted, two if you’re ill-fated to bear twins, is nothing compared to the midwife losing three children to the sea and throwing away the fourth. One St. Margaret Girl will tell a new Girl, and nearly all come to take for true that the midwife Lotte Jansen has sacrificed her children for them. Sinner and savior in one. You can identify with her. Though you’re not as craven a sinner. Or as selfless a savior. You have been longing for this saint, your own patron saint. You steal items she has touched—a comb a pencil a spoon. Stow them away. Relics.

Still, a few Girls fear the midwife’s power more than God’s. To Him they can pray for a stillborn; jump rope till they fall; probe with knitting needles to dislodge the parasite that has grafted itself to their insides; leap from the roof of the aviary and break both legs.

* * *

Sister Hildegunde paints countless versions of the mansion, some set on Nordstrand, some in Burgdorf where she grew up. Gradually those two landscapes morph into one: a sea that flows like a river; a river that fills the horizon. Dikes shelter both landscapes from floods. She gives the mansion wings so enormous she hears them flapping and feels blasts of wind. Barges and whirlpools she paints; flocks of nuns and flocks of babies; bridges and willows teeming with finches and monkeys and peacocks. What remains the same is how the mansion levitates on layers of mist.

“It doesn’t have to be like it was,” she teaches her students.

* * *

Inspired by the eternal feud between humans and sea, Sister Hildegunde finally captures the wild beauty of flooding in Hochwasser. If humans were to halt, the sea would surge forward, drowning their fields, their sheep, their families.

Hochwasser. And with it the abandoning of all you’ve worked for.

Hochwasser. It will herd you to the mainland, perhaps come after you as it often does in a nightmare.

* * *

Sister Hildegunde discovers Wilhelm in front of the dragon painting, looking up, though his hands cover his eyes.

“Such a funny dragon,” she says. “Let’s show our teeth to the funny dragon.”

Wilhelm watches her through spread fingers.

“Like this.” Sister pulls back her lips and hisses.

Wilhelm pulls back his lips and hisses. Drops his hands and hisses louder.

“Most excellent,” says Sister Hildegunde. “Now let’s roar at the funny dragon.”

“Moooooooo,” Wilhelm roars, eyes wide-wide open, roars like the dragon. “Moooooooo.”

And that’s how Sister Hildegunde will paint him, this boy facing a dragon, both roaring.

41

Nineteen Days

The beekeeper gets up during the night, fetches hot water from the boiler in the Kachelofen that’s set into the wall between the kitchen and parlor. He pours the water over dried chamomile blossoms, stirs in rapeseed honey, sits alone at the kitchen table with the cup between his palms, and raises it to his lips.

I know this.

Because one night I hear him. I get up to sit with him. Across from him and the steam from his cup and the wide span of his hands around the cup. Where does the warmth of his hands leave off and the warmth of the tea begin?

We talk about Heike, worry about her as if we were her parents. Between him and me there is a constancy I haven’t known with men. And yet, it feels familiar because it’s been there for me with women. With Luzia. With Lotte. A constancy and a comfort.

* * *

I make sure he sees me enter the path between the tall grasses, and I linger until he steps from the house. Then I let him find me. Wait for him to pretend he doesn’t know I’m here. That’s before I know that he does not pretend. He tells me he saw the bobbing of my shoulders and head above the grasses, always a few turns ahead of him.

We spread out my shawl, a flicker of threads, and when we lie down, the weave adapts to our bodies and the space between them, rearranges itself in hues of purples and blue.

“Now I know why the bees came to us,” I tell him.

“Why?”

“So that I had to summon you.”

In mist like this, you are gorgeous. It smoothes your skin. Makes your hair glisten. Mist is content to hold you, shrink your surroundings, lets you see the hidden till you emerge stunned, changed. For that’s the quality of mist. Waves and wind may rage, but mist does not need to show off.

We don’t talk about what we’re doing. Because then we’d have to stop.

From then on, I listen for him at night, sit up against my pillow so I won’t be caught by sleep. Soon, he is steeping two cups of his tea. Mine waits for me when I join him.

He slants the honey jar toward me. Rapeseed honey flows toward the edge of the rim.

“People will say…”

“Say what, Sabine?”

“That this is how I keep you for my daughter.”

“You’re making a sacrifice then.” He teases me.

“Being with you is no sacrifice.”

“What else will people say?”

“That I was searching for a man to keep Heike from harm if I were to die.”

“I’ll keep both of you from harm.”

“I would never take you away from Heike.”

“I don’t matter to her.”

“But if she wanted you—”

“It was never about her, Sabine.”

“For me it’s always about her.”

“I know that. But for me she is a child.”

After a few weeks of this—

* * *

No—

Nineteen days.

I remember exactly.

After nineteen days of this we stand up from the table and go to my room and lock the door.

Who has the right to say what should and should not touch?

&n

bsp; How many of you have longed for desire to overtake you once again?

For the rush of your beauty to amaze you?

Who is to say what is sin?

We’re discreet. Of course we are discreet. In public we hold one another with our presence, not with touch. And it’s even more exquisite like that because only we know. That’s how I have him for myself. He tells me he did not expect the passion that claims him, crazes him. For me such passion is instinctive. I show him. You tuck your toes beneath my feet, press them upward against my soles while your palms press downward against the crest of my head, and as you sink into me, bordering me inside and out, I strain against that sweet hold, break through with a cry.

42

Steadiness of a Thief

The Old Women are the guardians of legends. The Jansen children have entered legend. Definitely. The suicide of Herr Doktor Ullrich is gossip. The Nebelfrau—fog woman—has belonged to legend since before all time. Since before Rungholt. She can hide anything with Nebel. Confuse you. But if you look deeply into her Nebel, she will reveal the unseen to you. For some that’s courage.

* * *

“Eighty-five Hail Marys,” Maria Ullrich volunteers when the Old Women meet at her big house. Lace tablecloth and napkins. Her best silver. Candles though it’s the middle of the day.

“That’s nothing,” says Frau Bauer. “He gave me a headache.”

“In addition to the headache.”

“Twelve Our Fathers.”

“Three of each.”

“Eine ziemlich unschuldige Woche?” A fairly innocent week?

“I got done sinning when I was a girl.”

“True enough.”

Maria pours coffee into her porcelain cups. Hand-painted by her dead husband’s grandmother. Used only on Christmas Eve. But now every day. Despite her creased cheeks and neck, she feels more inside her beauty than when she was a young woman.

“I bet the beekeeper and Sabine got fifty Hail Marys,” says Frau Bauer.

“And fifty Our Fathers.”

“So let them. I get bored searching for what is sin and what is not.”

“The church’s way of keeping us timid.”

“Timid? Good luck with that.”

“If they tell you it’s a sin you won’t do it.”

“Hah!”

“Or not as often.”

“But eighty-five Hail Marys? Whatever did you do, Maria?”

Maria whispers, “Would you like to know?”

“Yes.”

“If I wanted you to know…”

They lean toward her. “Yes?”

“… then I would tell you—not some priest.”

“Oh—”

“You can be so…”

“… exasperating.”

“Stubborn,” Maria corrects them. “Stubborn.”

* * *

“Did you know the saintliest men sin the best?” I ask the beekeeper.

“And do I?”

“What?”

“Sin the best?”

“Oh yes,” I murmur against his throat. “It was mystical, the way you came into our wagon…”

“For the bees?” he teases.

“For me.”

“What if I was the one who sent the bees to invade you? Courting you with the sweetness of my honey.”

“Courting both of us?”

“You. It was always you, Sabine.”

I raise myself on one elbow, bring my face above his, and am stunned because my skin feels looser than when I lie beneath him. With The Sensational Sebastian I never thought of that; but now, with a lover a dozen years younger, I feel my features sag toward his. Is that what he sees? Quickly, I roll on my back. Feel my features adjust to gravity. Pat my cheeks and neck. Firm now.

He kisses my breast. “What if you outlive me?”

“One of us, then, the one who’s left over, will watch over her.”

* * *

The beekeeper talks to me while I’m sewing, lets me know if he’ll be away all day, or if he is hurt or puzzled. He talks to me before saying anything to Heike. And I listen. Assure him. Don’t let on I’m worried he’ll leave Heike. Fear has found a new target.

When he can’t find his amethyst letter opener, I offer to help him search for it.

“No, it was in my life a long time. I was fortunate. I expect losses. My first impulse is to get over a loss in a way that won’t take away dignity.”

“Dignity?”

“From others and from myself. It would be naïve to expect loss to bypass me.”

“I tend to hold on.”

He nods.

“Were you always like this?”

“Ja.”

“You must have been wise from the time you were a child.”

“It gets easier to lose things … even people. That’s why I dared marry your daughter.”

“You have the steadiness of a saint—”

“—of a thief.”

“A thief of what?”

“Books. I steal them from the library. It started when I was ten and the spine of my favorite Greek legends was torn. After I glued it to make it last, I returned it to the library. But that night I couldn’t sleep because I was afraid others would tear it up again.”

“You were a child.”

“I took it without borrowing.”

“You were a child!”

“I wanted to keep it safe for a few days or a few weeks and then take it back to the library and put it on a shelf when no one was looking. But I couldn’t … other books too. Later.”

“Always books that were torn?”

He nods. “I confessed to the priest. Still, I couldn’t stop.”

“Some of the greatest readers of the world stole books.”

“How do you know that?”

“Everyone knows.”

“No proof.”

“It must have been like that.”

He laughs. “Oh, Sabine.”

“You still do it?”

“No.”

I purse my lips. Wait.

“Not entire books. I take a piece of twine with me. If I want a certain page, say, I put the twine inside my mouth till it’s wet and then insert it on that page next to the binding. After it soaks through, the page comes out.”

Spit and missing pages. Disgusting. I see the pages with puckered edges Heike and I have found, the bits of twine we emptied from his pockets. “How about readers who check out those books after you’re through?”

“I take only a few pages. In a respectful manner that preserves the books.”

Respectful?

He watches me intensely.

Waiting for me to praise him for his thoughtfulness?

“We all lie to ourselves. This is just how you do it.”

He looks surprised. “I don’t lie to myself.”

“Of course you don’t,” I say quickly. After all, this is his house. And I must not let myself forget that. “I’m talking about the lies people come to believe about themselves. Lies they make up to spite or boast or get what they want.”

“Do you lie to yourself, Sabine?”

* * *

“What did you answer him?” Lotte says when I tell her.

“I put on my most mysterious smile for him.”

We’re in her kitchen, making Venetian candy with honey from our hives while Heike and Wilhelm and Tilli build bridges and houses with building blocks and feathers.

“I want to see that mysterious smile.”

I demonstrate. Smile with my lips closed. Hold it.

She turns her eyes to the ceiling as if struck by some divine insight.

“What?”

“That … is not mysterious.”

“Yes, it is.”

“Looks like sour stomach to me.”

“The Sensational Sebastian said my smile is mysterious.”

“Of course. Everything that man said was true.”

I pretend to frown, but I have to laugh.

“Not from him. But about him. Still a trapeze artist but always for a different Zirkus. Bremen. Köln. Danzig. Running from one woman while chasing after the next, telling her she’s not like other women.”

“That’s supposed to be a compliment?”

“It’s his line. I tried to prove him wrong.”

“Do you ever wonder how many other children he has fathered?”

“Abandoned.”

“True. He never was a father to your Heike.”

“Probably starts a new child with each new woman. Until he gets too old for the trapeze and stays with one woman for so long that, indeed, he turns to stone.”

“More, tell me more.” Lotte is fascinated and revolted by him.

“You’re far too interested in him.”

“I confess. Now tell me more.”

“We need more feathers,” Tilli announces from the door.

“Feathers for my hat,” Heike says. “A hat like Tilli’s.”

“Me too,” Wilhelm says as Tilli bundles him up.

“Stay together,” I say, though Tilli does that instinctively.

“A hat with a million feathers,” Heike says.

“Beautiful,” Lotte says.

* * *

“So … one day the Ludwig Zirkus sets up in a village where his statue stands in a square, bird shit on his shoulders…”

“… and you go up to The Sensational Sebastian and—”

“I don’t want to.”

“Just imagine…”

I don’t want to think about The Sensational Sebastian, but for Lotte I will. I’ll stand on my head to make her my best friend. Sometimes I believe she already is, but that doesn’t last.

“So…” Lotte prompts.

“So…” I sigh theatrically. Clasp my hands to my breasts. “Let’s say I’m with the Ludwigs that day they find his statue.”

“Don’t forget the bird shit all over him,” Lotte says.

Ursula Hegi the Burgdorf Cycle Boxed Set

Ursula Hegi the Burgdorf Cycle Boxed Set The Worst Thing I've Done

The Worst Thing I've Done Stones From the River

Stones From the River Hotel of the Saints

Hotel of the Saints The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls

The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls