- Home

- Ursula Hegi

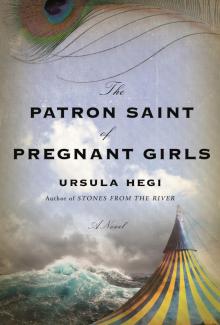

The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls Page 5

The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls Read online

Page 5

“I envision a convent with a school for young girls who get pregnant and must leave home.”

Her father blushed. “I didn’t know you were interested in that…”

“Sister Franziska trained as a midwife. I thought of an art school, but Sister Franziska says we can have both. We’re committed to help those girls and their—”

“Why is that?” her mother asked.

“To change what’ll happen to them. To give them a safe place where they can wait for their babies, surrounded by art. Of course they’ll also get an academic education.”

“So where do you envision this school?” asked her father.

“I’ve been thinking of our vacations up north … of clouds and rain.”

“Easy on your skin.” Her mother smiled. “You loved the Nordsee.”

Waltraud’s eyes drifted toward each other and she trained them toward the outer corners, willed them to settle as her Opa taught her, the only other albino in her ancestry. “That abandoned mansion by the dike…”

“I wonder if anyone lives there now,” said her father.

“It’s too big for you,” said her mother.

“Other Sisters will join us.”

“When?”

“Eventually … Soon … And there’ll be the students.”

Her father nodded. “We can find out, Waltraud.”

“We’ll have an infirmary. A nurse, too. Well—almost a nurse. Sister Konstanze didn’t have time to finish nursing school before she entered the convent.”

“We must set up a trust to protect the property,” her mother said.

“Why?”

“To block the church from taking possession.”

“Just please make sure the trust reads: Sister Hildegunde.”

9

St. Margaret and the Dragon

When the Sisters agree to name the mansion St. Margaret Home, after the patron saint of pregnant women, Sister Hildegunde prays for enlightenment. She slides her bone-white hands out of her sleeves, builds a wooden frame, stretches canvas across it, and sets up her easel in the dimmest alcove of the chapel. There, inspired, she paints St. Margaret, a martyr who defied the devil when he attacked her disguised as a dragon.

She hangs her painting in the dining room, astonished the Girls are scared of the dragon.

“St. Margaret isn’t even in the painting.”

“Yes, she is.”

“Where?”

Sister Hildegunde points to the dragon’s wide open teeth. “He swallowed her. Don’t you see her hands holding the crucifix that sticks from his jaws?”

“How do I know it’s her?”

“I’m the one who put her there.”

“Did you paint her face inside him?”

“No, but—”

“I hear her scream.”

“Her eyes are scared.”

“Is she dead, Sister Hildegunde?”

“No, no. It is the dragon who will die.”

“But she is the one stuck inside him.”

The Girls shudder, try to laugh.

* * *

In her alcove, Sister Hildegunde approaches the painting again. She considers the cross in the patron saint’s hands, a cross big enough to club a rabbit, say, or a chicken; but not a dragon. She enlarges it. Twice. To prove the dragon’s internal bleeding from this cross, she dabs crimson to the dragon’s jaw and chest before she summons the Girls.

“You don’t need to be afraid. St. Margaret’s cross has sharp edges that will destroy the dragon’s guts.”

“But the cross is on the outside.”

She sighs. “Once he swallows a little bit more of St. Margaret, the cross will be inside and cut him. He’ll start heaving till he vomits her out.”

“I vomited for three months,” says one Girl.

“I vomited for five months,” says another. “It began with a discomfort in my throat…”

“That dragon already killed the saint dead.”

“… a discomfort that’s more tenderness than irritation, a tenderness in the upper front part of my throat … just below my jaw that began as soon as I found out that I was no longer not-pregnant…”

The other Girls roll their eyes as she drones on. Even her prayers are endless inventories of what she’s done wrong in thought and in action, and what she could have done better in thought and in action.

“That saint won’t come out.”

“Except in bloody lumps.”

They shiver.

“This cross I painted,” Sister Hildegunde says, “will save St. Margaret’s life. I made sure of that. See how the shape of her body bulges from the dragon’s front? That means she is about to emerge unharmed to defeat the dragon.”

But the Girls cannot picture their patron saint inside the dragon. Hands with a cross are not enough.

“That bulge can be anything.”

Palms stroking bellies.

“A baby dragon.”

They giggle. “Or his tail.”

* * *

The Sisters whisper about Sister Hildegunde as they have ever since she singled them out to teach at her art school: that she’s too young to lead them; that she’s haughty. They question if she truly has a calling or became a nun because light stings her bone-white skin. Habit and wimple may shield her, but she still has to turn from the sun.

Her art is so bizarre that they must be tactful in their responses. Usually an approving nod will do without involving the sin of lying. Anything to do with praise, they can say aloud to her: how awed they are by her power to get this mansion for them; how grateful that she’s chosen them to relocate to this timeless snippet of land in 1842.

But this dragon needs intervention.

Sister Elinor: “She needs to know that the Girls don’t want to go into the dining room.”

Sister Konstanze: “If our Girls don’t eat, they’ll get sick, and that’ll harm the babies, too.”

Sister Franziska: “True.”

The Other Sisters: (nodding, although, sometimes, they don’t appreciate her directness and irreverence) “So true.”

Sister Franziska: “Let’s vote for one of us to talk to her.”

Sister Konstanze: “Not me.”

Sister Ida: (in her scratchy whisper) “She can kick us out.”

Sister Elinor: “She never has.”

Sister Ida: “She’ll call us ungrateful.”

Sister Franziska: “She’s spoiled.”

The Other Sisters: “Of course Sister Hildegunde is spoiled. And not one of us dares say it aloud.”

Sister Konstanze: “Then how do we tell her the painting is grotesque?”

Sister Ida: “Let’s leave her an anonymous note.”

Sister Konstanze: (leans against Sister Ida) “You don’t mean that.”

Sister Ida: “A short and polite note that her painting is leading to the starvation of our patients. It’s only practical.”

Sister Franziska: “Practical is not always the most compelling approach.”

Sister Ida: “Compelling? What about truthful.”

Sister Konstanze: “You can be so … sneaky.”

Sister Ida: “You promised not to say that anymore.”

Sister Elinor: “I suggest we vote.”

Four sets of eyes on her.

Sister Elinor: “Oh no. No.”

Four hands up. Quickly, the Sisters nominate Sister Elinor to be the messenger. The one most enlightened, they say, the only one of them born in the previous century.

* * *

But the intervention is a catastrophe. Sister Hildegunde stumbles back from Sister Elinor’s words, seized by such nausea that she cannot go near her easel. It gets so bad that she won’t enter the chapel for Mass or for vespers.

“The dragon terrifies the Girls,” she confesses to the priest. “Some of the Sisters, too.”

“May I see it?”

She hesitates.

He knows her by her confessions. Knows all the Sisters by their conf

essions: Sister Ida is secretive; Sister Elinor takes pride in her body; Sister Konstanze prefers birds to humans; Sister Franziska is greedy; Sister Hildegunde is brilliant but not arrogant as others see her.

“I cannot go back into the chapel,” Sister Hildegunde says.

He curves his fingers around her elbow. Gently. “I’ll stay with you.”

As he studies the dragon blood and the dragon teeth and the dragon gore, he thinks what tragedy it is when the desire to create is stronger than the talent. “Such tragedy…”

Sister Hildegunde holds her breath.

“Such … a depiction of tragedy.”

“Thank you.”

He reaches inside his cassock, brings out an ironed handkerchief and unwraps two Makronen, keeps one for himself. “Someone left them for me in the confessional.”

Sister Hildegunde takes a nibble. “They see the dragon. We see the saint.”

As a young priest he cleansed her soul, traveled every weekend from Husum to Nordstrand—on foot and by ferry—to hold Mass and hear confessions of Sisters and Girls and parishioners. Troubled by the opulence of the St. Margaret Home, he asked the young Sisters not to spoil him with lavish meals and lodging. In his own calling he strived for humility and was proud when he achieved it. Yet, he felt slighted by the plain food and the spartan room in the carriage house where he could reach every wall with his arms extended. Here, the young priest prayed for God’s guidance: if the Sisters were to serve him one lavish meal—just one, dear God—that was not in keeping with his humble lifestyle, he would submit to God’s will and consume this lavish meal so that it wouldn’t be wasted.

“Do you ever ask for what you like best?” asks Sister Hildegunde, a fleck of coconut on her upper lip.

“I can’t think of anything.” Schokoladenplätzchen und Marzipan und Lebkuchen und Linzer Torte und Spekulatius …

“But if … what would you ask for?” Her skin the palest of all skins, luminous—

—and his pulse a drum, a kettledrum. He points to the dragon and St. Margaret. “A powerful work of art…”

“Thank you.”

“… but perhaps—”

“Tell me.”

“—too powerful? For these young souls already traumatized? They see the dragon. We see the saint.”

Sister Hildegunde is swamped with pity for these young souls. “I can make St. Margaret more welcoming.”

“Welcoming…?” The priest is seized by coughing and covers his mouth.

She whacks his back between his shoulder blades. Whacks again. And again. And the fire of her hands throughout his flesh a celestial union this is where I live where I truly live—

She opens her lips for another nibble. “If only the Girls could see what you see.”

10

Sister Hildegunde Confronts Her Dragon

A week before the anniversary of the Sisters’ arrival, the priest invites the parishioners to the first annual recital and exhibit. “A momentous day for all of us at the St. Margaret Home, the culmination of our mission to educate our students in the arts—”

Whispering from the center church pews. Scoffing.

“In addition, of course,” the priest adds quickly, “in religion and scholarly subjects. One week from today, at seven, we welcome you to celebrate the achievements of our faculty and our students. Theater and dance and music. Paintings and tapestries. We’ll serve refreshments.”

More scoffing and whispering.

The Girls are sweating.

The priest is sweating. “Such scrumptious refreshments,” he says.

Sister Ida turns in her pew and glares at the scoffers and the whisperers. Raises her index finger to her lips and gathers herself for a fierce soprano that comes out as a hoarse whistle. “Ssshhhh … ssshhhh … ssshhhh…”

“Ssshhhh…” Sister Elinor adds her voice. A deep contralto. “Ssshhhh … ssshhhh…”

Silence from the center pews. But the Girls are giddy with adoration for Sister Elinor and Sister Ida who’ve taught them the range of the singing voice, let them play with extremes—screech and growl. For months the Sisters have rehearsed with them, studied and discussed, encouraged each Girl to choose her own area of performance.

* * *

Long before the curtain opens, the Girls take position onstage. During their rehearsals they’ve performed music and theater and poetry with joy, confidence, absorbing every new Girl into the recital. Everyone has a part. But now they hope the people of Nordstrand have forgotten about the recital. Hope the curtain will stay closed. The faint hum of an audience, and Sister Ida tugs at the curtain—

—opening it? already?—

No, finding the middle so she can peek through the gap. “We need a little more time.”

Sister Hildegunde rushes backstage, talks to the Sisters, then approaches the Girls. “My parents are excited about your recital. They’ve traveled a long way.” She nods to Sister Elinor.

Sister Elinor cringes. “Good news … we have a small audience tonight.”

“Such a relief.” Sister Ida laughs, but her eyes are angry. “That means fewer palpitations for all of us.”

The Sisters step away, and when the curtain opens, they already sit in the front row with other Sisters, the priest, and two old people the Girls don’t know, applauding and applauding, though nothing has happened yet. The Girls are ashamed, something the Sisters forgot to consider, ashamed to display their bodies onstage for outsiders to judge. Applause again when the recital ends, mild applause that matches their accomplishment.

But it’s not the end of the evening yet. The Sisters pack the uneaten refreshments into baskets and all set out with blankets and with lanterns for a feast on the dike. One Girl starts singing, then others. Two recite poetry. What has been excruciating onstage becomes playful, fluid. Lights and laughter bob toward the moon on their ascent.

* * *

Infants are born and Girls leave and new Girls and finches reproduce. Only a few Girls take their babies home with them, and the Sisters try to find families who’ll adopt the rest of the babies. Sadly, there are always more babies than families. When the nursery gets too crowded, the Sisters separate it into two: Little Nursery on the ground floor and Big Nursery on the second floor.

It’s not that easy to accommodate all the finches. The Sisters house them in the peacocks’ aviary; however, the gaps between the bars are too wide, and the Sisters visit the toy factory with drawings of cages, some small, others wide enough for several finches. In Sister Konstanze’s tapestry class, Girls braid long grasses into cocoons for inside the cages, and the Sisters trade finches with the people of Nordstrand for sourdough starter and geraniums, honey and eggs.

Storks build nests on steeples and chimneys while Sister Hildegunde confronts her dragon, mixing earth colors on her board—umber and sienna and ocher—layering and covering until her painting looks so muddy that it can be mistaken for an ancient canvas stashed for centuries in a bell tower. Or in a potato cellar, Sister Hildegunde thinks, and decides to stop painting.

She still teaches art but without passion. Her students believe it’s because they’ve offended Sister’s dragon and are cautious with her, shield her from seeing how bored they are with her art theories. Her confessions, too, are without passion—no spite or doubts—causing others to fear she’s fading altogether.

When the priest asks Sister Elinor for advice, she assures him the Sisters are watching closely.

“Her skin is paler than ever.”

“I know. And she is too thin.”

“She won’t look me in the eye.”

“She is not interested in you.”

His head snaps up.

“Or in me,” she says.

“Oh.”

“She is not interested in herself.”

* * *

It’s the priest’s idea to engage Sister Hildegunde in training St. Margaret Girls to become Kindermädchen—nursemaids.

“Once they leave here, there isn

’t much for them. But if we qualify them as Kindermädchen it will guarantee good work for them,” he tells her.

She trains her pale eyes on his left shoulder. “More of a chance.”

“True. They’re learning important skills here. They already know how to care for babies. But think of their advantage, Sister Hildegunde—how many mothers-to-be get to practice on so many babies?”

“It is a unique situation. But there is risk in exposing our Girls to so many infants. What if they become enamored with them? What if they want to keep their own?”

“We must be more aware of that.”

“Work together to prevent it.”

He blushes. “We’ll draw up guidelines for a Praktikum. List everything the Girls already do—feeding children and bathing children and keeping children safe—”

“And learning…” Sister folds her hands in prayer. “As part of the Praktikum.”

He leans toward her. Smells incense and turpentine and something else he can’t name. “You mean instruct children in basic learning?”

“And in the arts. Music and painting and weaving. We’ll issue a certificate that qualifies each to take care of an entire family.” She fingers his sleeve just above his wrist.

He tries to exhale.

“I’ll write each a letter of recommendation,” she says eagerly.

“Brilliant!”

“On fancy parchment.”

“Embossed.”

* * *

“Too much to do for any Girl,” the Sisters say when Sister Hildegunde presents the plan.

“True,” she agrees. “That’s why our certificate will list what they’ve learned to do. Not what they do every day.”

“What certificate?”

“A certificate to make them more employable. After they complete a Praktikum.”

Three months later the priest writes to priests in other parishes to recommend the new Kindermädchen. “They are qualified to bathe children, feed children, swaddle children, protect children, instruct children in early learning and music and painting. Their skills will benefit the entire family, including cooking, canning, baking, cleaning, washing, ironing, and sewing. They have successfully completed our classes and Praktikum and have earned their certificate as Kindermädchen.”

Ursula Hegi the Burgdorf Cycle Boxed Set

Ursula Hegi the Burgdorf Cycle Boxed Set The Worst Thing I've Done

The Worst Thing I've Done Stones From the River

Stones From the River Hotel of the Saints

Hotel of the Saints The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls

The Patron Saint of Pregnant Girls